|

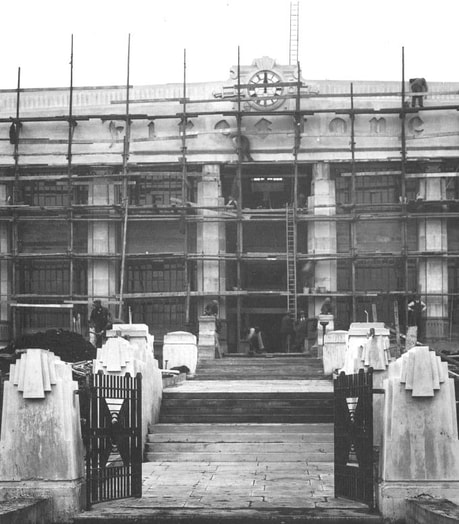

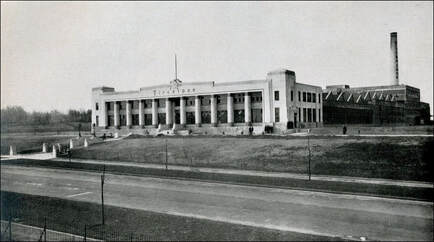

Sunday August 23rd 2020 is the 40th anniversary of the demolition of the Firestone Factory on the Great West Road in Brentford. It is an event which sparked a backlash against the quick demolition of such buildings (although it did not stop them) and galvanised the growing consensus around preserving 20th Century buildings. We shall explore the building itself and its design, and the aftermath of its demolition. The American Firestone Tire & Rubber Company had run a distribution base from Tottenham Court Road from 1915, but the 33.3% import tax was reducing their profit margin. By 1928 they had decided to build a British factory, and a 28 acre site alongside the newly opened Great West Road running out of Brentford was chosen. The plot was bounded by road, railway and canal, with the road frontage measuring 1260 feet, sloping down to the carriageway. Firestone wanted an integrated site, with raw goods being received and making their way through the factory and leaving as the finished product. Their factory in Akron, Ohio, built by Osborn Engineering, was designed to extract maximum efficiency from the journey of the raw material through the industrial process. In awarding the commission to Wallis, Gilbert & Partners, Firestone employed a practice who understood this idea. By the late 1920s, Wallis, Gilbert & Partners had already been practicing for around 12 years, designing factories and industrial buildings all over Britain. Two of those buildings were in nearby Hayes, for the Gramophone Company and Hayes Cocoa, but the Firestone commission was to be their most prestigious project yet. The design, which was submitted in February 1928 and altered over the next 6 months, consisted of a main administration block facing the Great West Road with the single storey factory building behind and a four storey dispatch and storage building further back. The journey of the raw material started in this four storey block, journeying through the production block before exiting as tyres back through the four storey building. Of course it is the art deco office building which people conjure up when they think of the Firestone building. The building was to act not just as an administration centre but also as an advert for the company and for what we would these days call its “brand”, looking to project speed, glamour and aspiration. The building was a mix of Classical allusions. In plan it was a Greek or Roman temple with its row of columns along the frontage, in detail it was Egyptian, with references to the gods Horus, Ra and Amun in its decoration. Egyptian design was still popular 6 years after the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun by Howard Carter in 1922. By night the building was floodlit, producing a spectacular landmark along the Great West Road. Despite the lamentations at the time of its demise, and indeed now, the Firestone Factory was not always feted by the architectural press. After initial good notices when it was opened, the building and others designed by the firm were described by architect Maxwell Fry as displaying “all the worst sentimentalities of uncultured commercialism”, whilst others worried about the effect of soot and dust on the brilliant white facades. Firestone decided to close the factory in November 1979, moving all operations to their Wrexham plant, with the building being purchased by the conglomerate Trafalgar House. When they became aware that the Department of the Environment under Michael Heseltine was planning to list the building after the August Bank Holiday weekend in 1980, they immediately acted to demolish the art deco facade. This act caused widespread outrage, and boosted the profile of what was then The Thirties Society, now the 20th Century Society. It also caused a reassessment of the listing criteria for 20th Century buildings, allowing many more pre-1939 buildings to be preserved. Now all that survives of the building is the gateway and perimeter fence, although there are three other Wallis, Gilbert & Partners designs nearby; the Coty Factory, the Pyrene Factory and the Sir William Burnett workshop. Of course, the Firestone Factory wasn't the only art deco building demolished along this stretch. A peruse of the area on the Britain from Above website reveals a number of interesting looking buildings of the period, all now sadly gone. However, the Firestone Factory did not die in vain, its demolition led to a renewal of interest in buildings of period and their preservation, enabling us to enjoy some of the great designs of Wallis, Gilbert and Partners from the golden age of factory design.

The 20th Century Society still plays an important role in preserving the best buildings of the last 100 years. Help it prevent more demolitions like the Firestone Factory by becoming a member HERE References Form and Fancy by Joan Skinner London: North West by Nikolas Pevsner and Bridget Cherry

7 Comments

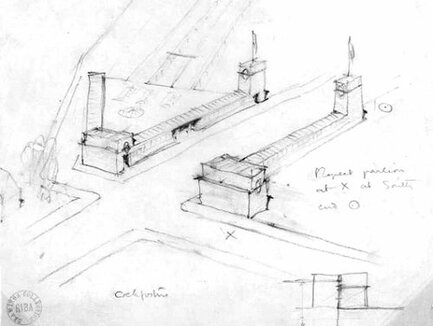

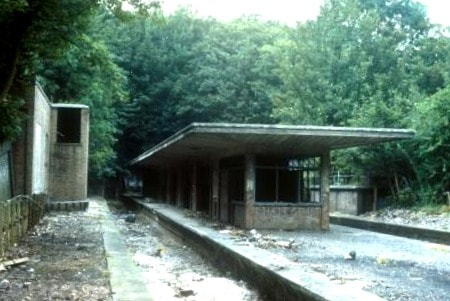

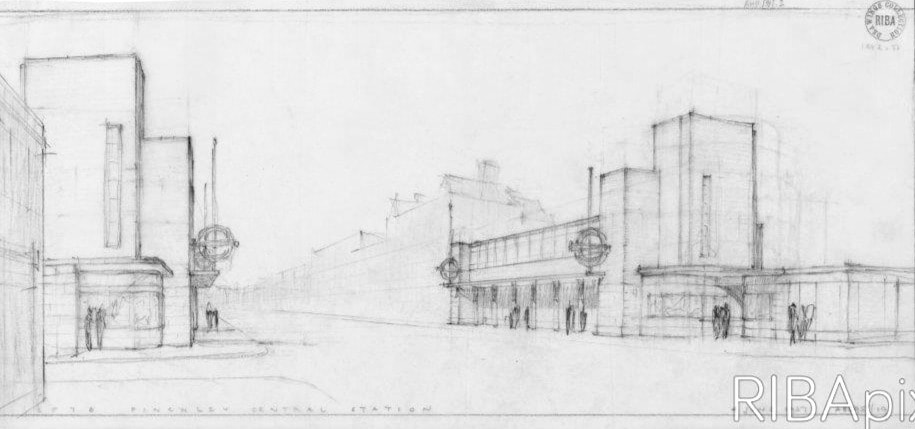

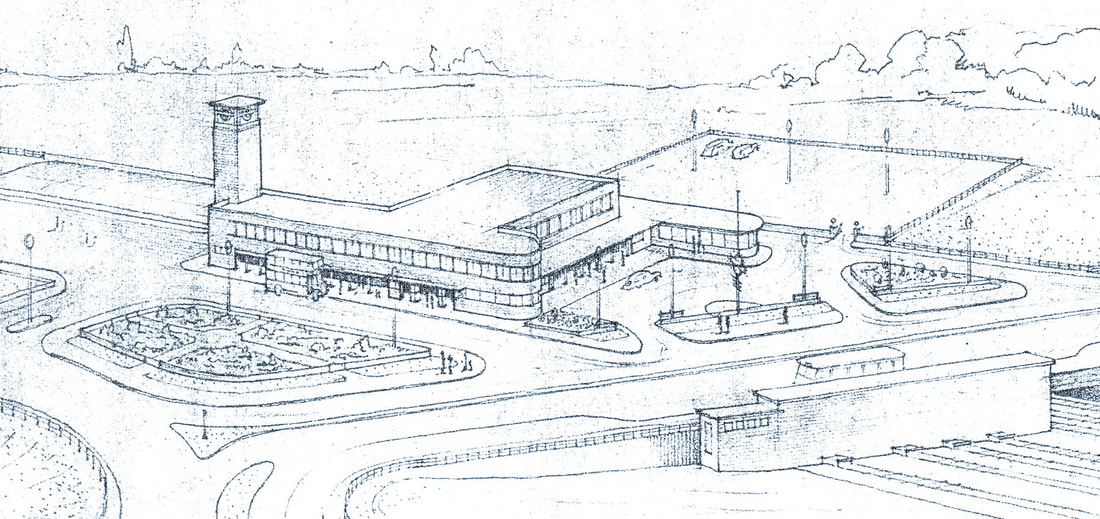

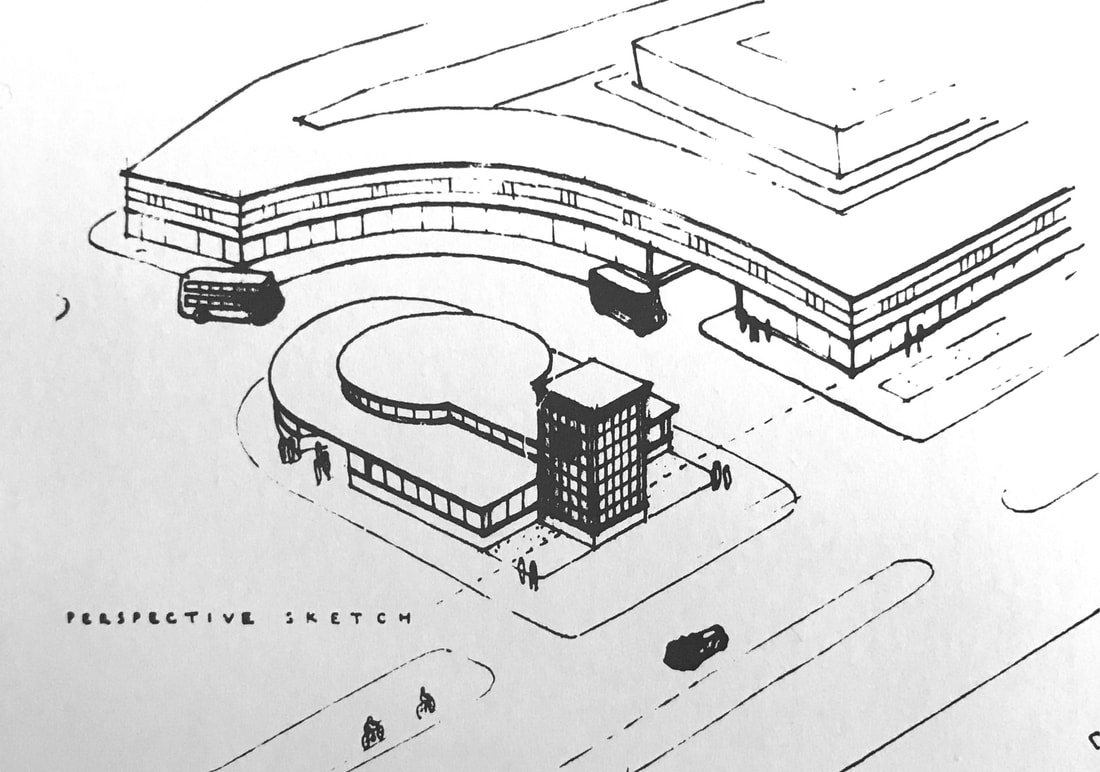

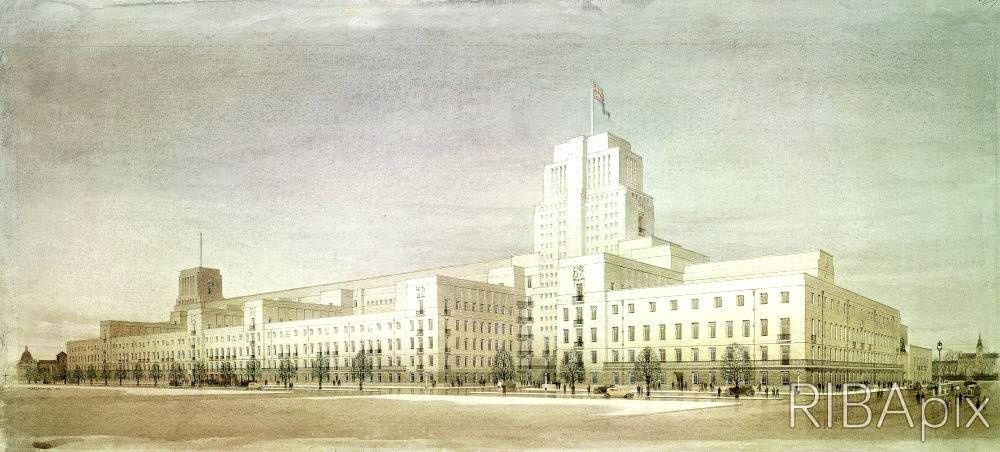

This website is very fond of celebrating the work of Charles Holden for London Underground in the 1920s and 30s. His designs brought modernism to the suburbs, especially the extensions for the Northern and Piccadilly Lines. Holden designed about 44 underground stations, the majority of which are now listed. However, there are a number of station designs which didn't get built, and it is those we will investigate here. The majority of the unbuilt Holden designs for London Underground centre around the New Works Programme of 1935-40, and the cancelled Northern Heights project This was meant to extend the Northern Line further north than its terminals at High Barnet and Edgware. But there are a few unbuilt projects from earlier in Holden’s relationship with the underground. Holden’s first underground stations came as part of the Northern Line extension to Modern, designing 8 stations that were completed between 1925-26. Not long after in 1928, Holden and his practice, Adams, Holden & Pearson, were asked to design a station for the Central Line that would have been called Notting Hill Gate. It would have stood on the corner of Notting Hill Gate and Pembridge Gardens, and the design is similar to Holden’s for Bond St station the same year, a simple facade in brick and stone. Further west, Holden was asked to design a new station at Hounslow East, having also designed Hounslow West in 1931. Holden’s design here was a “Sudbury Box” style station with a tower that abutted the above ground railway viaduct, just as at Alperton. The station design was approved by London Underground CEO Frank Pick in June 1931, but construction never started. The station retained its 1909 station building until 2003 when it was replaced by a new station by Acanthus Lawrence and Wrightson Architects. On the other branch of the westen Piccadilly line to Uxbridge, Holden had developed a modular station design that could be used at different locations along the extension. This was never used, like Holden’s various designs for a station building on the awkward site at Hillingdon, where again the old station building survived until 1993, when it was replaced by the new station by Cassidy Taggart. One more Piccadilly station worth mentioning is Cockfosters. Opened in 1933, the station as built has modest street level buildings with one of Holden’s best interiors at platform level; all exposed concrete, looking forward to post war brutalism. The original plan for the station would have seen two brick towers either side of the Cockfosters Road, where the current buildings are, a grand terminus building for the new settlements around Trent Park that were stopped by the Green Belt Act. As mentioned earlier, the Northern Heights plan was to extend the Northern Line into Hertfordshire, pushing on from Barnet and Edgware, as well as integrating former London & North Eastern Railway (LNER) lines to the underground service. This was to be achieved under the New Works Programme of 1935-40, which looked to expand various tube lines and replace existing stations with modern designs. Highgate station would have been a connecting hub between the Northern Line and the LNER service. The site where the current and proposed station is situated is very awkward, on a sloping site on Highgate Hill. Stanley Heaps, chief architect for London Underground, produced a design with a hexagonal station building before Holden produced his designs. Holden’s designs would have encompassed a street level ticket hall with a circular tower, and then a long escalator ride down to the new platforms which were topped by a 12 ft high statue of Dick Whittington. Revisions were made to this design, and construction commenced in January 1939, with the station starting service a year later. However war time privations struck hard and building was stopped in March 1942. Post war, the design was strpped back to the basics and officially opened in August 1957. The island platforms are still intact and can be visited through the London Transport Museum Hidden London tours. A few stops north, Finchley Station station was to be redesigned, with a new station replacing the Victorian era building. Holden designed a number of schemes alongside New Zealand architect Reginald Uren, who would design Rayners Lane station alongside Holden. The various plans situated buildings either side of Ballards Lane, usually with a number of towers, sometimes glazed at street level. For reasons unknown the rebuilding project was never started, and the original station is still there. The extension of the Edgware branch of the Northern Line would have bought new stations at Brockley Hill, Elstree South and Bushey Heath. Brockley Hill station was to be designed between the office of Stanley Heaps and the planning office of All Souls College, owner of some of the land the extension would pass through. It was to be built on a viaduct next to Edgware Way, and would have incorporated a curving forecourt of shops. Work on the viaduct was started in 1939 but abandoned due to the outbreak of war. Remains of the viaduct can still be seen between the Edgware Way roundabout and Edgwarebury Brook. Holden was asked to design the two stations after Brockley Hill, at Elstree South and Bushey Heath. Elstree South would have been located further along the Edgware Way, just north of the area that would become the M1 motorway. As usual a few different designs were produced, the last one featured a station sitting over the tracks with a Chiswick Park style square tower. A statue of a figure in Roman dress was also to have been included in the site, alluding to the nearby Roman settlement of Sulloniacis. Bushey Heath station would have been the end of the extension, and located west of Elstree South next to the A41 roundabout. The building would have been in the centre of a new development, built to incorporate the expected continuation of the 1930s housing. Of course World War II and the Green Belt Act put paid to this sprawl. No firm plans were made, either by Holden or Heaps successor Thomas Bilbow, but various amenities were to have been included in the scheme including a pub, a cinema and a parade of shops. No construction was ever started on the scheme, and the Northern Heights project was officially canceled in 1950. As well as the unbuilt stations, there are a few what-ifs in Holden’s designs for the eastwards Central Line extension. As part of the New Works Programme from 1935-40, Holden was asked to design 3 stations at Wanstead, Redbridge and Gants Hill. Building was started on all three stations prior to World War 2, but put on hold when men and materials became scarce. When construction restarted after the war, Holden’s original designs were revised to cut costs. Wanstead was originally to have glass bricks forming part of the ticket hall and its tower, along with a carving of St George and the Dragon by Joseph Armitage. The final design jettisoned these in favour of austere prefabricated concrete panels finished in grey render, with black tiles around the station entrance. The design for Redbridge was to take the glass theme even further, with an almost totally translucent ticket hall, and an all glass tower incorporating a glass etching from the Paris 1937 Exposition. Obviously this would prove too expensive post war, so the building was finished with brick and tile. Thankfully the next station along, Gants Hill was less affected by shortages, with its Moscow Metro inspired platform area left alone. What it did lose, was a brick clock tower at street level, that would have sat in the roundabout above the underground ticket hall. Of course, Holden’s most famous unbuilt project is his designs for the University of London. Holden had been appointed to design a new complex of buildings for the University, who wanted to move from Kensington. Holden designed a proto-groundscraper, covering the whole area from Montague Place to Torrington Street. Construction was started in 1932, but funds for the whole project ran out, and the only completed part is now the Grade II* listed Senate House and Library. We have plenty of underground stations, and an array of other buildings like substations, signal boxes and depots,all designed by Charles Holden in the golden period between 1925 and 1940, but it's always interesting to think of what might have been…. Next stop Elstree South! References Bright Underground Spaces by David Lawrence Underground History website A Guide to Modernism in Metro-Land, our guidebook to help you discover the suburbs best art deco, modernist & brutalist buildings. Go HERE to get your copy.

|

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed