|

After the success of our Open House Stanmore tours last year, we will be holding a walking tour of some of Charles Holden’s Piccadilly Line stations on Saturday May 14th. Starting at Turnpike Lane and working our way up to the terminus at Cockfosters, we will be looking at some of Holden’s most iconic London Transport work. Taking in the stations of Turnpike Lane, Wood Green, Bounds Green, Arnos Grove, Southgate, Oakwood and Cockfosters, we will also note other modernist buildings along the way, such as Curtis and Burchett's work for Middlesex County Council. To coincide with the anniversary of Charles Holden’s birth on May 12th, the tour will take place on Saturday May 14th at 10.30 AM. Tickets are £10 per person (plus booking fee), and can be booked here https://www.ticketsource.co.uk/date/242990 . The tour will be limited to 25 people, so book early! The route will be a mixture of walking and tube, so please bring a topped up Oyster card/contactless credit or debit card and a pair of comfortable walking shoes, plus any refreshments you may need. The tour should take approximately 2.5-3 hours. If there is sufficient interest in this tour, we will also host a visit to some of the western extension Piccadilly Line stations in July, to celebrate the 85th anniversary of the opening of Sudbury Town station. If you have any questions about these tours please email [email protected] or use the reply form below.

0 Comments

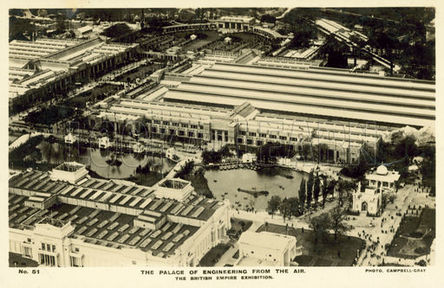

The career of Owen Williams took in both triumph and disaster, moving from purely functional engineering projects to more expressionist, proto-brutalist buildings. Williams would produce a huge range of buildings and constructions over his fifty year working period, producing motorways, factories, aircraft hangars, offices, apartment blocks, health centres and much much more. He was a driving force in the construction of twentieth century Britain, and a pioneer in the use of a material that would define the post war city, concrete. Evan Owen Williams was born in Tottenham in 1890, to a Welsh mother and father who had moved to North London to open a grocers shop. While serving an apprenticeship at the Metropolitan Electric Tramways Company, Williams studied Engineering by night class, eventually earning first class honours, before going to work for two engineering firms, Indented Bar & Concrete Engineering and then Trussed Steel Engineering. It was at these companies that Williams got to use and experiment with reinforced concrete, and explore its architectural possibilities. The first known building he was involved with was the Gramophone Factory in Hayes in 1913. A functional, six storey building, it has none of the adornments of most factories of its era, and looks forward to the modernist factory of the twenties and thirties, and across to the pioneering European factories of Peter Behrens and Gropius & Meyer. The building is still standing and now Grade II listed. Williams spent World War One designing experimental projects for the Admiralty, such flying boats and the use of concrete in ship building. After the war Williams set up his own company and became involved in a project that would end up gaining him a Knighthood, the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley. Designed to bring all corners of the Empire together and show the variety of its cultures and commerce, the Empire Exhibition was built on the site of Sir Edwin Watkins failed tower on the edge of north west London. Williams was chosen by the exhibition chief designer, Maxwell Ayrton, to assist in the creation of the Palaces of Industry, Engineering and Art. These buildings were not modernist in design, but were pioneering in terms of their concrete construction. The Palace of Engineering was the largest concrete building in the world at half a million square feet. The exhibition was a great success, with over 27 million visitors from its opening in 1924. However, very little remains of the site with all three Palaces now demolished. Williams did design a nearby building that has stood the test of time, the Empire Pool, now known as Wembley Arena. It was completed in 1933 for the following years Commonwealth Games (and later used for the 1948 and 2012 Olympic Games). Williams used concrete fins on the exterior of the building to support the massive roof over the pool area, and these and the water towers in each corner and the unabashed use of concrete, lends the building a fortress-like air. At this stage in his career Williams was riding the crest of a wave, with his Daily Express buildings in London and Manchester and the Pioneer Health Centre in Peckham, seen as exemplary modern buildings, balancing form and function. Probably William's greatest achievement is his work on the Boots Factory in Beeston. Built between 1930 and 1938, this factory complex is an integrated site that can be rearranged or extended as needed. It incorporates “Wet” and “Dry” areas as well as packing areas, offices, canteens and laboratories. Williams expressive use of concrete, as well as steel framed glazing, again pointed forward to the buildings of the post war period. The site is now Grade I listed and seen a masterpiece of the modern movement. However, not everything Williams touched turned to gold. His design for the Dollis Hill Synagogue (1938) was not well received by the congregation, and he was forced to return part of his fee. The building is one of Williams most stylised in design, the point at which he goes from being an engineer to an architect. Nevertheless, this reinforced concrete building is now Grade II listed and used as a primary school. Williams career never picked up the same momentum of the early thirties, although two of his greatest buildings would be built after the Second War War, the BOAC Maintenance HQ (1955) and the Daily Mirror building (1961). The BOAC building saw Williams using the skill he had deployed on the Boots factory, producing a complex consisting of four aircraft hangars, each measuring 102 metres by 43. Williams used his expertise with concrete construction to produce a building that is still in use at Heathrow 60 years later. The Daily Mirror was built at Holborn Circus in collaboration with Anderson, Foster and Wilcox,with Williams overseeing the engineering and construction, and the partnership designing the exterior and interiors. The finished building housed offices and printing presses and was the heart of the newspapers operations until 1994, when they moved to Canary Wharf. The building was demolished not long afterwards. Over his fifty year career, Owen Williams moved from being an engineer to the architect of some of Britains best modernist buildings. At his best he combined structural robustness and expressive design using just concrete and glass. The tension between engineering and architectural design was perfectly balanced in his best buildings, and it is only when he tried a more artistic style that he faltered. However he will be remembered as pioneer in the use of concrete and set a template for the way buildings would be built for the rest of the 20th century.

This article first appeared in The Modernist issue #14 ENGINEER |

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed