|

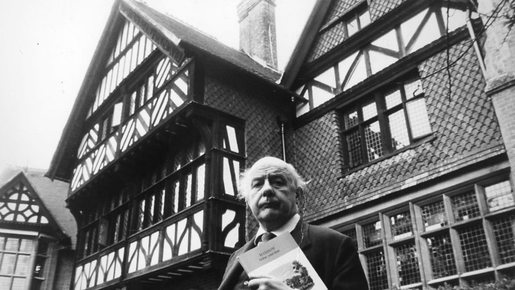

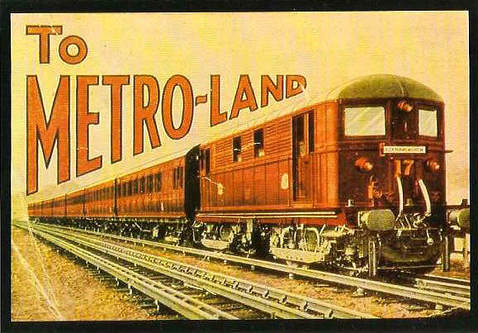

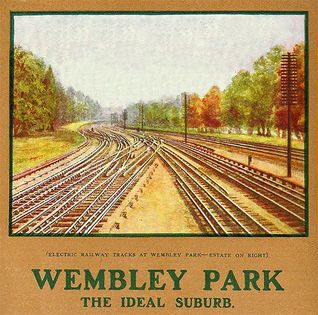

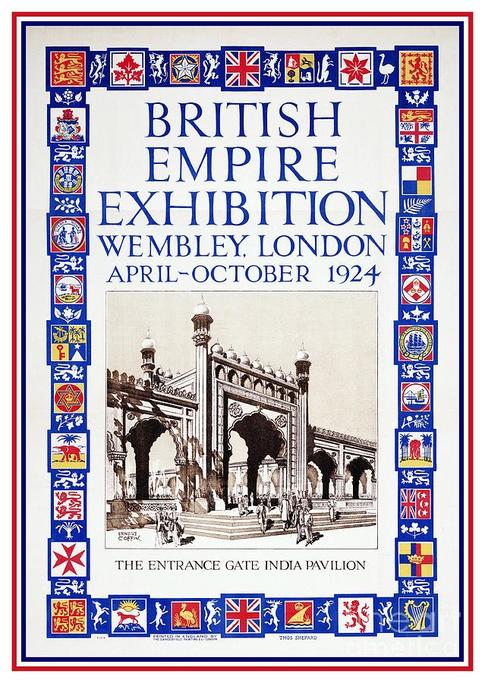

The documentary programme “Metro-Land”, written and presented by John Betjeman and directed by Edward Mirzoeff, was first aired 45 years ago this week, on 26th February 1973. Forty-nine minutes in length, the programme follows Betjeman as he travels the course of the former Metropolitan Railway, from the hustle and bustle of Baker Street to the abandoned station of Verney Junction, near Aylesbury. In between, Betjeman explores the north western suburbs of London, the area that became known as Metro-Land in the first part of the 20th Century. Betjeman had previously hymned Metro-Land’s praises in his poems such as “Harrow-on-the-Hill and Middlesex”. The then Poet Laureate takes in various buildings; from John Adams Acton’s neo-gothic house in St John's Wood, to Norman Shaw’s Arts & Crafts Grim’s Dyke in Harrow Weald and C.F. Voysey’s The Orchard in Chorleywood. And of course he also visits a few buildings that may be familiar to visitors to this website. The first of these is at Wembley, and the site of the 1924 British Empire Exhibition, now largely demolished. The exhibition was one of the engines that fueled the growth of Metro-Land, drawing 27 million visitors to the outskirts of London. Indeed Betjeman notes that before it Wembley was “an unimportant hamlet where the Met didn’t bother to stop”. The exhibition was built on the site of the 1890 tower known as “Watkins Folly”, an attempt by the railway magnate, Sir Edward Watkin, to construct a British version of the Eiffel Tower. The project ran out of money after the tower had reached just over 150 ft, and was abandoned before being demolished in 1907. The design and construction of the Empire Exhibition was handled by John Simpson, Maxwell Ayrton and Owen Williams. Among the many pavilions and halls were the Palaces of Arts, Industry and Engineering. Betjeman appears in the film in the first of these, as well as on the pitch of Wembley Stadium, also built as part of the Exhibition, and reminisces about attending the event Almost all of the exhibition buildings have now been demolished, with the Palace of Industry being torn down in 2013. You can read about the last surviving remnants HERE. Next was the decidedly un-modernist Highfort Court in Kingsbury. Designed by architect Ernest Trobridge, this personification of the saying “An Englishman’s home is his castle” sits at a crossroads amid a number of other Trobridge designed buildings. Trobridge believed in the healing powers of design and built his homes for those returning from the horrors of World War I. His house designs can be found all over what is now Brent, and are instantly recognisable from their faux-rustic appearances, using timber, brick and tile hanging to create a vision of the (non-existent) idyllic past. For the programme, Betjeman perched upon the battlements of the entrance, providing one of the most memorable images of the film. The most modernist piece of metro-land visited by Betjeman was High and Over house in Amersham. Designed by Amyas Connell, and completed in 1929, this house was one the first modernist houses in the country and one of the most infamous due to the publicity after it was built, as Betjeman says “..all Buckinghamshire was scandalised..” Connell designed the house for Professor Bernard Ashmole, then Professor of Art and Archaeology at the University of London. Connell and Ashmole met in Rome at the British School, were Connell had been A Rome Scholar. The house is arranged in a Y-plan, with three wings radiating from a hexagonal centre. The stark white walls, sun terraces areas and glazed staircase where all elements borrowed by Connell from contemporary European architecture, particularly Le Corbusier’s early house designs. Despite the appearance of solid concrete walls, as with many early modernist houses in Britain, it is in fact white rendered brick around a concrete frame. Connell's later partnership, Connell, Ward & Lucas, would design four smaller ‘Sun Houses’ on the slopes below High & Over in the 1930’s. Unfortunately the dramatic effect of these four modernist houses on the hill has been denuded by the 1960’s estate of detached houses now surrounding them, something Betjeman notes in the film. “Metro-Land” ends with Betjeman visiting the abandoned stations of Quainton Road and Verneys Junction, reminiscing over waiting for trains at the stations when it was still active and ending the documentary with the words “Grass triumphs. And I must say I’m rather glad”. Of course this wistfulness and melancholy was fully in keeping with Betjemans poetry and especially his later works. So while the ‘shock of the new’ wasn’t particularly new or shocking even when “Metro-Land” was filmed, it allows us to see some of Metro-lands modernist architecture along with the characters and traditions that make this region so interesting. We are hoping to tread in the footprints of John Betjeman in producing “ A Guide to Modernism in Metro-Land”, a guide to the art deco and modernist buildings of the region. Follow this link to help make this possible and see the great rewards for pledging Pledge for A Guide to Modernism in Metro-Land

1 Comment

|

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed