|

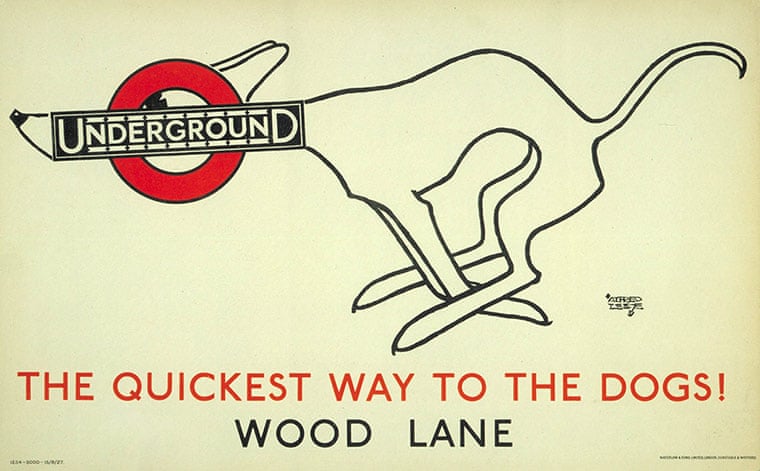

Last year we wrote a blog on our Modernist London sister site looking at the postwar rebuilding of Bethnal Green in East London. This time we venture west and explore how the White City area of Shepherds Bush reconstructed itself after World War II. The area was farmland until the railway companies bought trains and trams to the area from 1874. The “White City” name comes from the 1908 Franco British Exhibition held in the area, which featured pavilion structures clad in white marble. The only remnant of the exhibition is the Japanese Gardens on the other side of the old TV Centre. The same year the Olympic Games were held at White City, with a new stadium designed by engineer JJ Webster. It was famously used for greyhound racing as well as other sports until demolished in 1985 and replaced by BBC White City. During the War, the area was home to several Anti-aircraft batteries and an Air Defence HQ, and so was extensively bombed. This provided the basis for the extensive rebuilding of the area, something which had begun in the 1930s with the construction of the White City Estate by London County Council. The original plan was for an estate consisting of 2300 flats in 49 5-storey blocks, to house a population of 11,000. However the war halted construction, with a slimmed down plan completed in 1953 with a population of 8000. Design wise the estate is a typical London County Council 1930s design, and was somewhat anachronistic by the time it was completed, compared to the New Brutalist designs of estates like Alton West. The estate plan is partly influenced by Zeilenbau ideas, with blocks aligned along a north-south axis for maximum sunshine, with green spaces in between, and an east-west axis, Commonwealth Ave, with spaces for public buildings. The streets are named after countries featured in various exhibitions, such as Australia and Canada. One of the first buildings of the postwar era in the area was the new underground station for the area. White City Station, built to replace the old Wood Lane station, which opened in 1908. The new station building was built just to the north of the old station, opening on 23rd November 1947. It was designed by architects A.D. McGill and Keith Seymour, under the supervision of Thomas Bilbow, Chief Architect of London Transport. They produced a Charles Holden-like design, with a rectangular ticket hall, featuring large glass windows with a coloured roundel.The station won a Festival of Britain design award in 1951, and the Abram Games designed plaque can be seen to the left of the entrance. Another early postwar building was the new BBC Television Centre, built from 1951-60. It was designed by Graham Dawbarn of Norman & Dawbarn, with the plan of the building being a question mark shape, reportedly after Dawbarn drew a question mark on an envelope when starting his designs and realising it would be an ideal shape for the site. It is now Grade II listed and has been redeveloped for a mixture of studios and homes. New community buildings for the White City estate were added into the Zeilenbau grid. Opened as Canberra Infants and Juniors School in 1949, the now Ark Swift Academy is a conventional example of late 40s, early 50s London County Council school design. It is built in brick, and features ‘Festival’ details such as blue columns and external reliefs. Opposite the school is the church of St George and St Michael for 1953, designed by Seely and Paget to serve the estate. A Roman Catholic church, Our Lady of Fatima, was opened in 1966, designed by Wilfrid Cassidy. The most dramatic postwar building in this immediate area is Malabar Court, an old people's home designed by Noel Moffett & Partners in 1964. Built up of hexagonal units, allowing privacy and maximum sunlight for each resident. The home is constructed of concrete and brick infill, around a tall service column. Moffett designed similar old persons homes in Camden, Barnes, Twickenham, and two estates in Tower Hamlets. A little to the west is Phoenix Academy, built in 1958 as separate boys and girls schools, with shared facilities, Christopher Wren Boys' School and Hammersmith County Girls' School. The schools merged in 1982 and became Phoenix Academy in 2016. The school was built in brick and timber, which were used as other materials in short supply. It was the first job in charge for architect Edward Hollamby, who would go on to achieve great things as head of Lambeth Borough’s Architects Department and later the London Dockland Development Corporation. Hollamby was very much influenced by the Arts and Crafts architecture of the late 19th century, buying and restoring William Morris Red House in Bexleyheath. He used original Morris woodblocks to create a wallpaper pattern for the school, and comminsoned tapestry curtains designed by artist Gerald Holtom, featuring Morris, Rossetti and Burne-Jones. A new 6th form centre by Bond Bryan Architects, was opened in 2010. A later addition to the area is the Wood Lane Estate, opposite the tube station, designed by John Darbourne and Geoffrey Darke. Planned from 1973, the estate was completed in 1978. It features 140 dwellings for 550 people, and consists of brown brick terraces, of two and four storeys. All homes have their own front door at pedestrian level, with pedestrian access and private spaces emphasised. Darbourne & Darke are most famous for their Lillington Gardens estate in Pimlico, and other estates in Islington, Richmond and Clapham. In the 1960s the area became bounded by the Westway motorway extension to the north and Hammersmith Flyover to the south. The southern part of this area was also rebuilt in the 1950s and 60s. A church from 1872 on the Uxbridge Road was damaged by a bomb in WW2 and never properly repaired. Eventually it was replaced in 1978 by St Lukes, a new church, hall, vicarage and housing complex, designed by Hutchinson, Monk & Locke. The church features stained glass by John Hayward, and an interior of exposed brick and wooden fixtures and furnishings. Hutchinson, Monk & Locke formed in 1964, after winning a competition to design Paisley Civic Centre as students. Heading 5 minutes south to Westville Road, we find one of three schools by Erno Goldfinger from 1951. It was designed in a kit form, to be able to be used on a variety of sites, like the contemporary Herts County Council schools, built with exposed concrete and brick infill. The scheme features low, informally grouped buildings with large windows and a tall brick tower. Nearby is Flora Gardens, two blocks of flats comprising a total of 37 homes, designed for Hammersmith Borough by H.T. Cadbury-Brown with borough engineer J.E. Scrase. Cadbury-Brown had assisted Erno Goldfinger, as well as designing for the Festival of Britain and Harlow New Town, and later designed the Royal College of Art. The flats are designed in brick with exposed reinforced concrete floor slabs, and built by the borough’s Direct Labour Organization.

The postwar rebuilding project has itself been rebuilt in various waves since the 1980s, with White City and central Hammersmith continually in reconstruction mode. Hopefully this blog will serve as a reminder of the postwar buildings we may lose and the social, rather than monetary, thinking behind them.

1 Comment

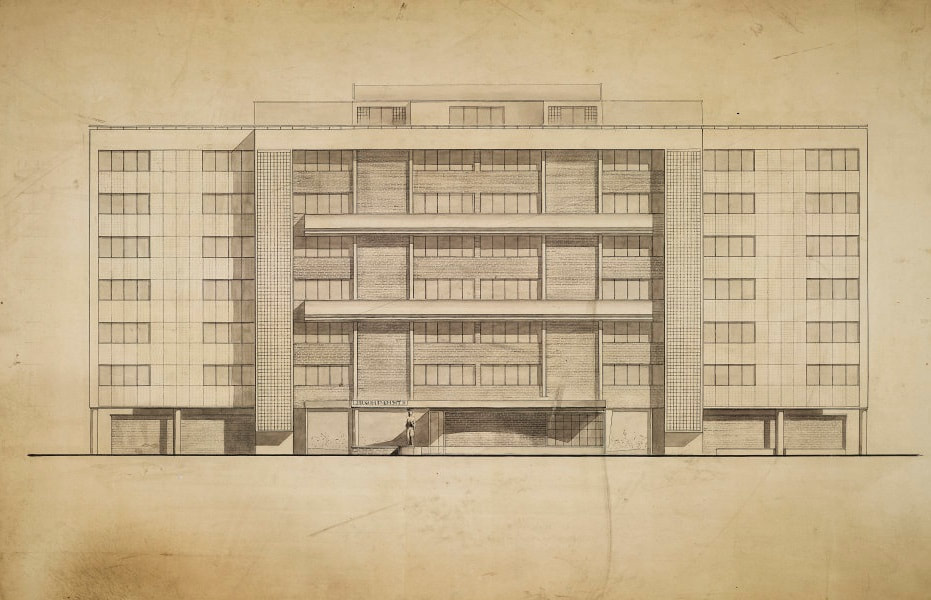

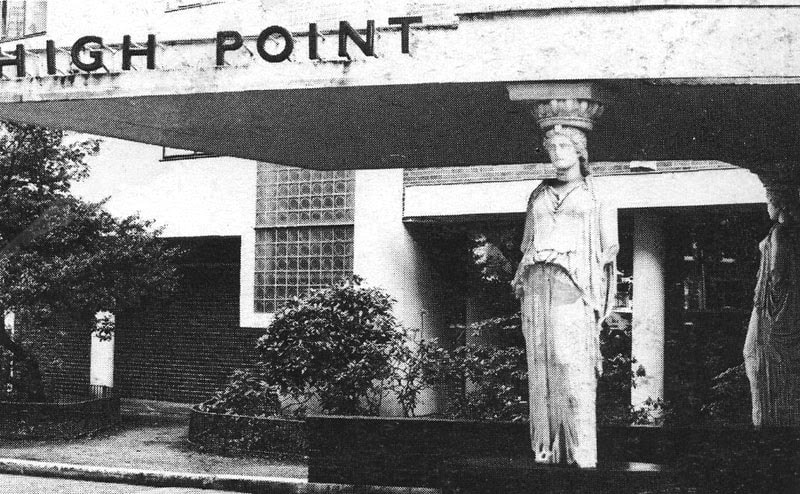

From his arrival in 1931 until his premature retirement in the 1960s, Berthold Lubetkin helped introduce modernist design to Britain through a range of innovative buildings. His first buildings in the UK were those for London Zoo, the Gorilla House and the Penguin Pool, whose white walls and curving lines became an icon of the city. The Finsbury Health Centre was a success for its architectural design as well as its moral purpose, built as part of the “Finsbury Plan”, a borough wide policy to combat common problems such as lice, ricketts and diphtheria. His subsequent housing estates for Finsbury and other municipal boroughs brought to life his maxim “Nothing is too good for the ordinary people”. The building that brought him and his architectural practice Tecton to the attention of the world's architectural press, was Highpoint, an international modernist style apartment block on Highgate Hill for businessman Sigmund Gestetner in 1935. Gestetner’s original plan was for the block to house workers for his nearby factory (Tecton would design a factory for him in 1937, since demolished). However, in a reversal of the maxim mentioned earlier, Highpoint appears to have been too good for the ordinary people. The first block, later known as Highpoint I, consisted of a seven storey, reinforced monolithic concrete structure containing 60 flats. Built between 1933-35, it was laid out in a double cruciform plan, eight flats to a floor. The two and three bedroom flats were arranged so the living rooms in each would receive light at some point during the day. The flats had the luxuries of central heating, a built-in refrigerator and shutes for disposing of dirty laundry, as well as a communal tearoom and a winter garden. Ove Arup oversaw the engineering for Highpoint, devising a system that reused the concrete shuttering as the building rose. The completed building was a critical success, with Le Corbusier visiting on behalf of the Architectural Review and declaring it “an achievement of the first rank”. The success of the first building led to another. Highpoint II was built on a piece of land Lubetkin had urged Gestetner to purchase to avoid encroaching developments. Built between 1936-38, the second building progressed on from the white walled minimalism of the first, by including brick and tile as exterior finishes. This was partly down to complaints from neighbouring residents at the dazzling whiteness of Highpoint I, and partly to guard against the inclemencies of the English weather. Highpoint II has fewer flats, with only 12 apartments and a penthouse (taken by Lubetkin), but was larger and more luxurious in materials, combining marble, pinewood and tiling throughout. The lifts in Highpoint II also bring residents straight to their apartment, with no intermediate lobby or hallway. One of the most interesting and surprising details is the use of two caryatids as support pillars for the entrance porch. They were cast using moulds borrowed from the British Museum. Their use signaled a move away from the functionality of Highpoint I, towards a more playful approach, using classical and surrealist references. The use of the caryatids and the more varied materials shocked the young modernist orthodoxs, with Lubetkin seeming to throw away the ideals he had written in concrete next door only a couple of years earlier. Like Highpoint I, the second block was a commercial success, prompting many more offers from developers for Tecton to design luxury flats. However Lubetkin and Tecton moved towards municipal architecture, starting with Finsbury Health centre and moving onto estates such as Priory Green, Spa Green and Bevin Court. Lubetkin's plan for Peterlee New Town was stymied by bureaucratic wrangling, and after the completion of the Dorset Estate for Bethnal Green Urban Borough, he retired to Bristol where he lived until his death in 1990.

|

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed