|

The Empire Swimming Pool and Arena was officially opened on 25th July 1934 by the Duke of Gloucester. It was built to be part of the 1934 Empire Games, and contained a pool measuring 200 feet by 60 feet, with facilities for ice skating. The stated aim of the building was to create a venue that would “create for Great Britain..the opportunity of establishing itself second to none in the swimming world”. The building, designed by Owen Williams, features three concrete span arches measuring 72 meters (236ft) with exterior supporting counterweight fins, and boxy water towers, giving it somewhat of a fortress-like air. The massive span arches avoid the need for internal pillars and give a maximum viewing field to spectators. The building of the Pool cost £150,000, the equivalent of £1.5 million today. The original design for the building had curved fins, but these were dropped to simplify construction. The east end of the building was designed to open up, and led to sunbathing terraces and lawns, which have now been removed. The structure was built on top of the ornamental lakes from the British Empire Exhibition, which Williams had been involved in the construction of 10 years earlier. The Pool faced what was originally known as the Empire Stadium, (later Wembley Stadium), and also designed by Owen Williams, along with John Simpson and Maxwell Ayrton. The idea for the arena came from businessman Arthur Elvin, who had bought the Empire Exhibition, including Wembley Stadium, in 1927. Elvin was keen to ensure the grounds continued being a tourist attraction, and so after making the stadium home to football he wanted to bring other sports to the area. As well as being part of the Empire Games, the arena was designed to hold ice hockey matches. After being used as part of the 1948 Olympics, it has come to be somewhat of a national treasure after its conversion to a popular concert venue. The building was Grade II listed in 1976, and since 1978 has been known as Wembley Arena. In 2012 it again hosted events for the Olympics, with badminton and rhythmic gymnastics taking place there.These days it is rather dwarfed by the various buildings going up around it, part of Brent Council’s remaking of the area. The Empire Pool, along with the Boots Factory buildings in Beeston, probably mark the highpoint of Williams journey from engineer to architect. Williams had had some notable failures in his career, (the Dorchester Hotel, Dollis Hill Synagogue, Warren Fields apartments), often when architectural pretensions obscured the brilliance of his engineering. However, at the Empire Pool at Wembley, he balances both the function and the form, producing one of the best examples of “the New Objectivity” and looking forward to the concrete extravaganzas of the post war era. References

London 3: North-West- Pevsner & Cherry The Design and Performance of the Empire Pool at Wembley- Roy Perlmutter and Robert Mark Owen Williams By David Yeomans, David Cottam

4 Comments

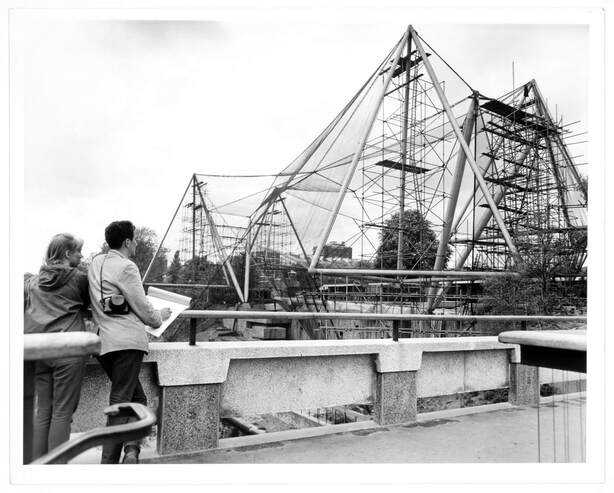

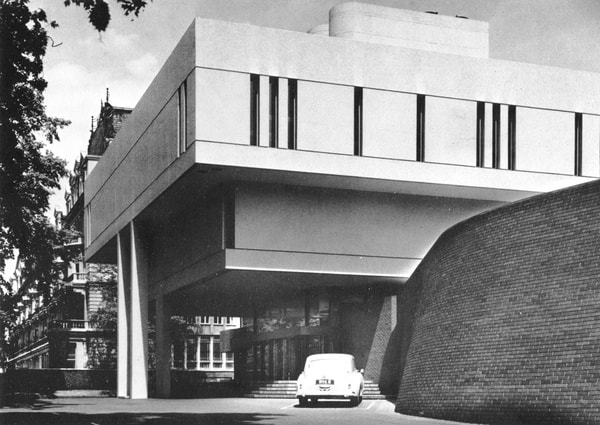

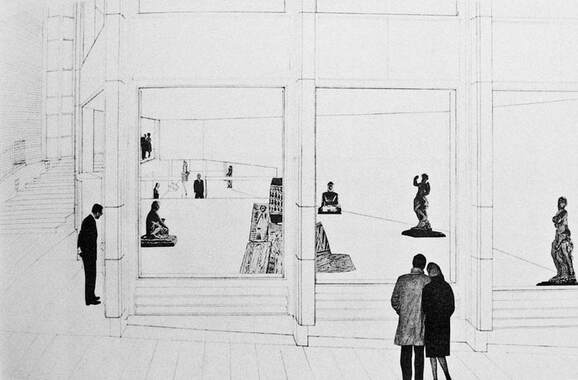

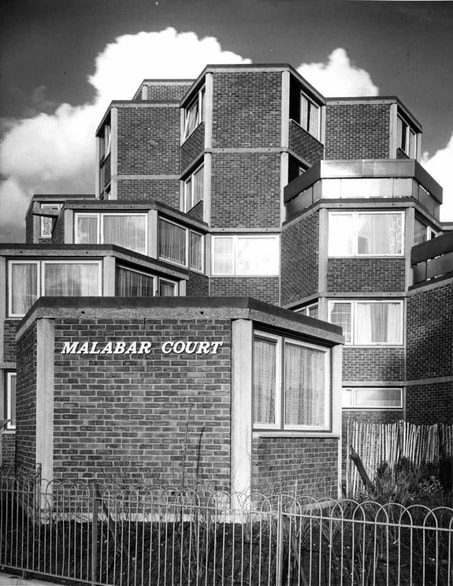

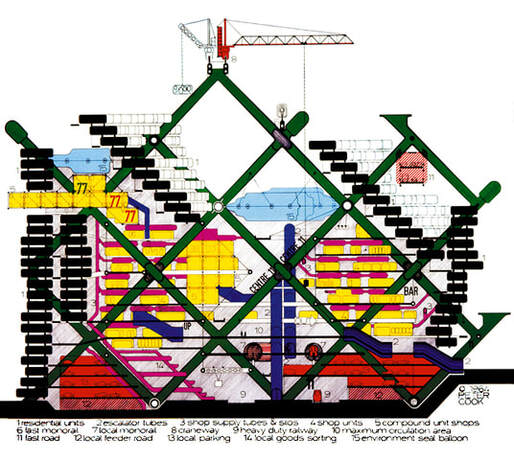

1964 saw the completion of a number of buildings in Britain that have gone on to be lauded as classic designs and listed, as well as influencing future architects. These buildings by Denys Lasdun, Basil Spence, Alison & Peter Smithson, Cedric Price and others have become exemplifiers of the era of the “White Heat of Technology”, the phrase made famous by Harold Wilson in his speech to Labour Party conference in Scarborough in 1963 (Wilson actually said “the white heat of this revolution” referring to the scientific advances of the time). Today this buildings are commonly labeled as “Brutalist” although their designers did not always feel kindly towards this term. The term brutalist has come to mean any large, concrete building from the 1960s and 70s, but the buildings we will examine from 1964 share a forward looking attitude, using a variety of materials in different forms and styles. Harold Wilson was elected Prime Minister in October 1964, in part as a result of that speech in Scarborough, which looked forward to a technological future rather than towards an imagined past. Other harbingers of the future that included the first broadcast of Top of the Pops on New Year's Day, the agreement to build a Channel Tunnel in February and the abolition of the death penalty in November. That gleaming beacon of technological progress, the Post Office Tower, was completed on 15th July (although it wouldn't come into service until October 1965). Looming nearly 600 ft over Bloomsbury, the communications tower designed by Eric Bedford of the Ministry of Works was built as part of a network of Ultra High Frequency transmission towers, designed to boost telephone, radio and television communications. The tower was sited in Howland Street where the Museum Telephone Exchange sat, a small site necessitating the need for a small construction footprint. The tower was designed with an observation deck and a revolving restaurant, which was leased to Billy Butlin of holiday camp fame. The observation decks were closed in 1971 after an IRA bomb explosion, and the restaurant closed in 1980. The tower was listed in 2003, and remains as a glimpse of a space age future that never quite arrived. A short distance away, another futuristic building was completed in 1964. What has become known as the Snowdon Aviary at London Zoo was completed in October. Although named after the photographer and then husband of Princess Margaret, who led the design team, the idea was brought to life by architect Cedric Price with Frank Newby of F.J. Samuely & Partners as the structural engineer. The structure is constructed of aluminium and steel, and arranged in four tetrahedra with steel cables holding the tubes and netting in place. The structure is designed to allow the birds room to fly and for a path through the space for visitors.The aviary is a clear forerunner to the High Tech buildings of the 1970’s and 80’s produced by Norman Foster, Michael Hopkins, Richard Rogers and others. Foster + Partners are currently renovating the aviary for the actual 21st century. Another building in the same vicinity as the Post Office Tower and the Snowdon Aviary, and also completed in 1964, is the Royal College of Physicians. Opened on November 5th, and designed by Denys Lasdun, this building on the edge of Regents Park has become one of the few post war buildings to achieve a Grade I listing. The building contains conference rooms, offices, a library, a lecture theatre and a dining room. A prestressed concrete frame forms the structure, with the lower volume of the building clad in dark brick and the upper in pale grey mosaic tiles, part of Lasdun’s brief for the building to fit in with the older terraces surrounding it. The overhanging volume containing the library is held up by three pillars. Inside the building balances everyday functions with ceremonial spaces, and features a freestanding staircase. Slightly further to the north than the previous trio of buildings is Swiss Cottage Library by Basil Spence, which was opened on November 10th by Queen Elizabeth II (she also opened another library by Spence the same week, at the University of Sussex). It was designed as part of a civic center planned for the borough of Hampstead. With the reorganisation of the London boroughs (the elections for the new boroughs was held in April 1964), only the library and swimming pool part of the plan was built , with the swimming baths and their William Mitchell concrete designs demolished in 2002. The library is a rounded lozenge shape, with three storeys above a basement book stack. The exterior features vertical fins of Portland stone, designed to control sunlight and muffle traffic noise. Between 2000-3, John McAslan & Partners refurbished the building and remodelled the site. Opening on December 10th was the Economist buildings on St. James Street, Westminster. The buildings were designed by Alison and Peter Smithson, who had brought brutalism to Britain with their school in Hunstanton, Norfolk in 1954. Here the Smithsons replaced an older set of buildings with three towers of varying height on a raised plaza, a piece of Chicago transplanted to higgledy piggledy Central London. The buildings are constructed around concrete frames with Portland sandstone facades and metal windows. The plaza featured work by Eduardo Paolozzi, and is itself formed of slabs of Portland stone. The scheme is now Grade II* listed and undergoing refurbishment by DSDHA. 1964 also saw the completion of a number of other modernist buildings of interest in Britain. Opposite Hampstead Heath, 9 West Heath Road by James Gowan was completed for furniture designer Chaim Schreiber, the house fitted with furniture also designed by Gowan. With its sombre appearance and strong vertical emphasis, it’s draws from the same language as the Economist buildings. Another private house completed that year is New House in Shipton-under-Wychwood, Oxfordshire. Designed by Stout and Litchfield for prominent London barrister Milton Grundy in 1964, New House has an interesting composition of five linked pavilions with mono pitch roofs, and a Japanese gravel garden. The house, constructed of local Cotswold stone, was Grade II listed in 1998. It was used in Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film of Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork Orange. A couple of apartment blocks from this year are also worth noting. Corringham in Craven Hill Gardens, Bayswater was designed by Kenneth Frampton alongside the firm of Douglas Stephen & Partners (whose own The Mount apartment block in Kensington was also competed in 1964). Internally, Corringham is arranged in a scissor plan, with each flat having split levels with bedrooms facing east and living rooms and kitchens facing west. Externally the block is formed of an exposed reinforced concrete frame, with prominent steel ventilation units. Further west in White City is Malabar Court, an old people's homes designed in a hexagonal form by Noel Moffett for the LCC. Moffett designed a number of social housing projects with distinctive hexagonal shapes or projecting balconies across London, most of which are still in use such as Ashington Court in Bethnal Green. Of course no mention of futuristic architecture in 1964 could be complete without mention of Archigram, the architectural design group known for their colour illustrations of projects that never got built. Two of their most famous ideas, the Plug In City and the Walking City were published in 1964 via their own magazine. Both ideas saw technological megastructures replace the traditional organic city, with buildings truly becoming “machines for living in”. These ideas would filter down to the next generation of architects, such as Richard Rogers and Nicholas Grimshaw, influencing their Hi Tech designs of the 80’s and 90’s. As we have seen, in 1964, the era of the “White Heat of Technology” was reflected by the completion of a number of buildings that would go on to be hugely influential and later on listed. Today they can be seen as moments to optimism and the belief in the power of technology to overcome the problems of humankind. That idea seems quaint nowadays, but these buildings live on to remind us that we can use architecture to reflect ideals rather than as just a way of creating capital. References

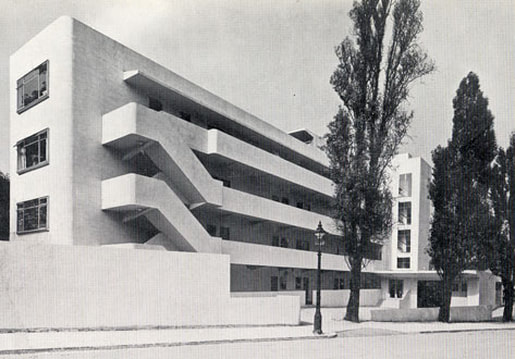

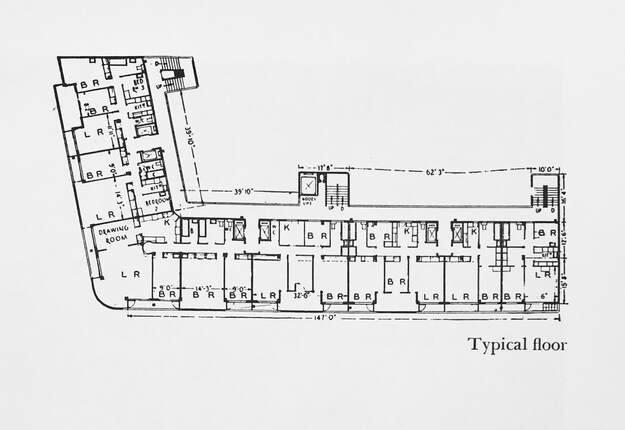

London 4 : North- Pevsner & Cherry London 3: North-West- Pevsner & Cherry Atlas of Brutalist Architecture British Buildings 1960-64 British Public Library Buildings- Beriman & Harrison This Tuesday July 9th 2019 sees the 85th anniversary of the official opening of the Isokon building on Lawn Road in Belsize Park. The stark modernist apartment block, also known as the Lawn Road Flats and designed by Wells Coates for Jack and Molly Pritchard, was declared open by Miss Thelma Cazalet (later Cazalet-Kier), an early British feminist and then Conservative MP for Islington East. Cazalet errounesley thanked “Russell Coates” for designing the building and broke a bottle of beer on the side of the Isokon to declare it open. Construction on the building had started in September 1933 after a stuttering fruition. The Pritchards had originally wanted a house for themselves on the site. The brief then changed to two houses, then to two houses and a nursery school before settling on an apartment block designed to provide inexpensive flats for young professionals. The finished building provided 22 flats for single people, named “minimum” apartments, as well as larger apartments, a caretaker's flat and the penthouse apartment occupied by the Pritchards. Inside, the flats were fitted out with space and labour saving fixtures and fittings, including sliding tables, electric cookers and lighting. The furniture was mostly in plywood and manufactured by the Venesta furniture company, who Jack Pritchard worked for. Food was also available from the communal kitchen, first as room service then as part of the Isobar, converted by Marcel Breuer and FRS Yorke in 1936. Breuer was an early tenant of the building alongside Walter Gropius, Arthur Korn, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and later on novelist Agatha Christie. Externally the building was formed of reinforced concrete, using the 10ft 8in module which reflected the width of the flat's main room. This meant no internal supporting columns were needed, allowing the spaces to be open plan and flexible. Like most interwar concrete buildings, the Isokon suffered from weather related deterioration, with the roof, walls and windows needing repair after World War II. The postwar period was not kind to the building. After being sold to the New Statesman magazine, the building passed into the ownership of Camden Council in 1972, falling into disrepair, becoming essentially derelict and abandoned by the 1990’s. As part of a competition, the building was acquired by the Notting Hill Home Ownership Housing Association and refurbished by Avanti Architects. The building now provides 25 flats as shared ownership to key workers, and 11 flats for sale. The building was Grade I Listed in 1999, and the former garage was converted into the Isokon Gallery in 2014, as a permanent display (open Weekends, March to October) telling the story of the building and its inhabitants. Today, the rejuvenated Isokon building stands as a monument to an earlier age, when the idea of designing an avant garde yet affordable building was not a pipe dream, as well as reminding us of the impact of one of the earliest modernist buildings in the country.

|

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed