|

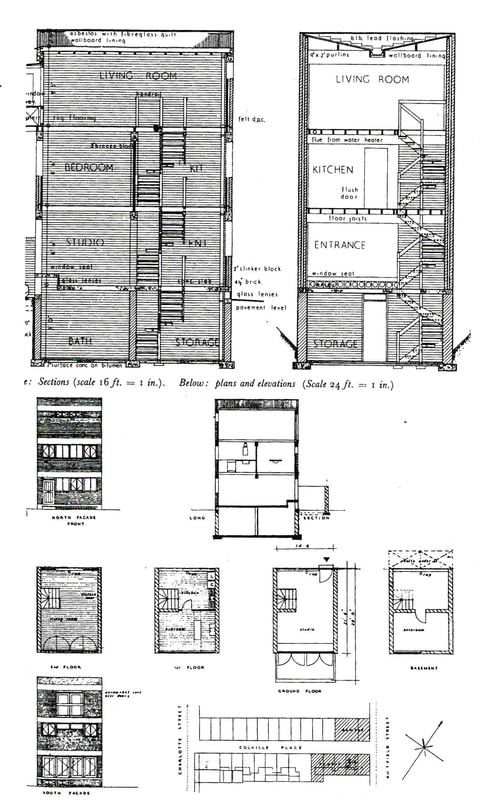

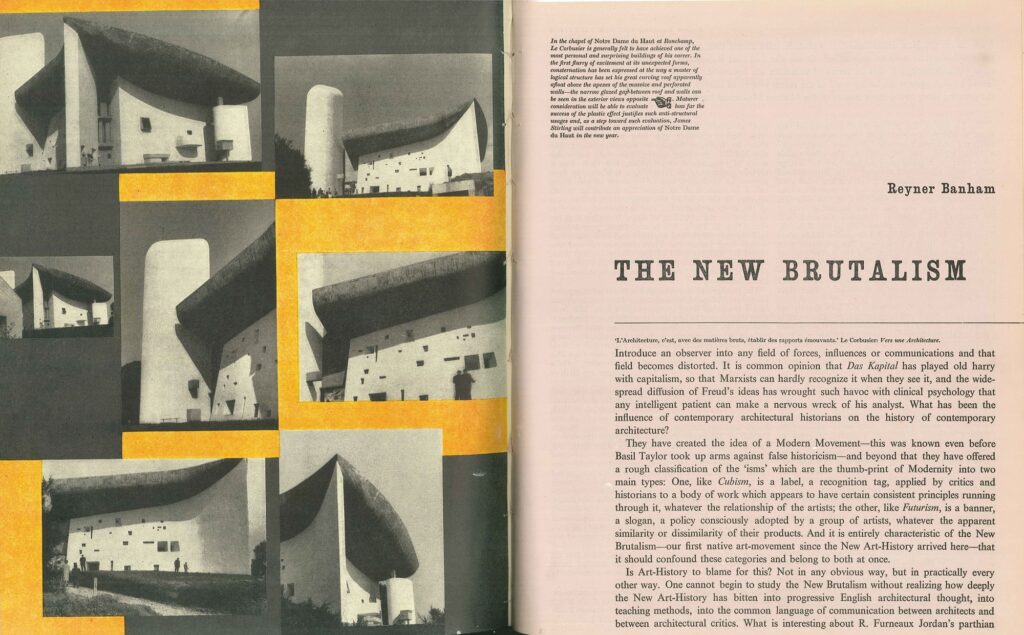

In December 1955 The Architectural Review published an essay by Reyner Banham titled “The New Brutalism”, which defined for the first time, the bold, new architecture emerging from Britain and Europe in reaction to the watered down modernism of the immediate post war period. The word Brutalism had been used two years before by Alison Smithson in Architectural Design when describing a project for a house in Soho. The origin of the term “Brutalism” has a few different origin stories, from the straightforward (from Breton Brut, the French term for raw concrete) to the more fanciful (an amalgamation of Peter Smithson’s nickname, Brutus, and Alison’s name). The term Brutalism has come to mean any concrete building built in the postwar period, but to begin with it was much more specific, much more of a philosophy than a design guide. The main idea was “truth to materials”, i.e. not disguising the concrete or brick or steel being used in the construction of the building, but making the materials an integral part of its appearance. Banham summarizes Brutalism as “1, Formal legibility of plan; 2, clear exhibition of structure, and 3, valuation of materials for their inherent qualities 'as found'." Banham’s 1966 book, The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic?, brought together influences on Brutalism such as Le Corbusier and Owen Williams, and examples from around the world. The British examples included buildings by the Smithsons, Yorke, Rosenberg & Mardall, Denys Lasdun, Owen Luder, Lyons, Israel & Ellis, John Voelcker and many others. Banham was born in Norwich in 1922, and after an engineering scholarship studied at the Coulthard Institute of Arts, where Nikolaus Pevsner was one of his tutors. He was employed by the Architectural Review in 1952, where he wrote “The New Brutalism”. His criticism and theories were very influential on the post war architectural scene, through his journalism and books such as “The Well Tempered Environment”, “Theory and Design in the First Machine Age” and “Megastructures”. Banham would also go on to teach at the Bartlett, UCL and the University of California. He died in London in 1988. Brutalism fell out of architectural fashion in the 1970s as architects and local authorities moved away from tower blocks to smaller, less uniform designs, and the oil crisis hit, making it more expensive to build on such a scale. Its reappreciation at the start of the 21st century has seen its praises sung in books and blogs, on social media and even on tea towels, but it is still a highly divisive term, much misused by both friends and foes. So it is worth reminding ourselves where it came from and what it originally meant, 65 years after Banham’s article.

You can read the original article HERE

1 Comment

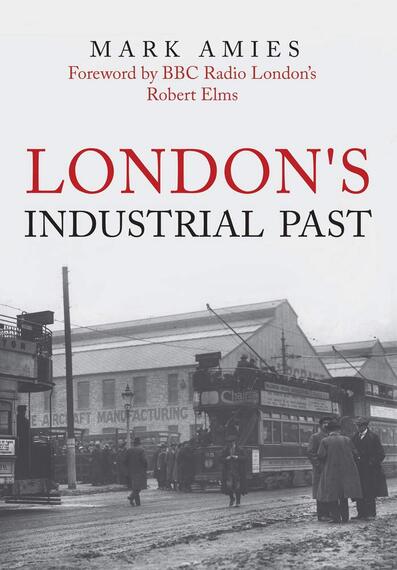

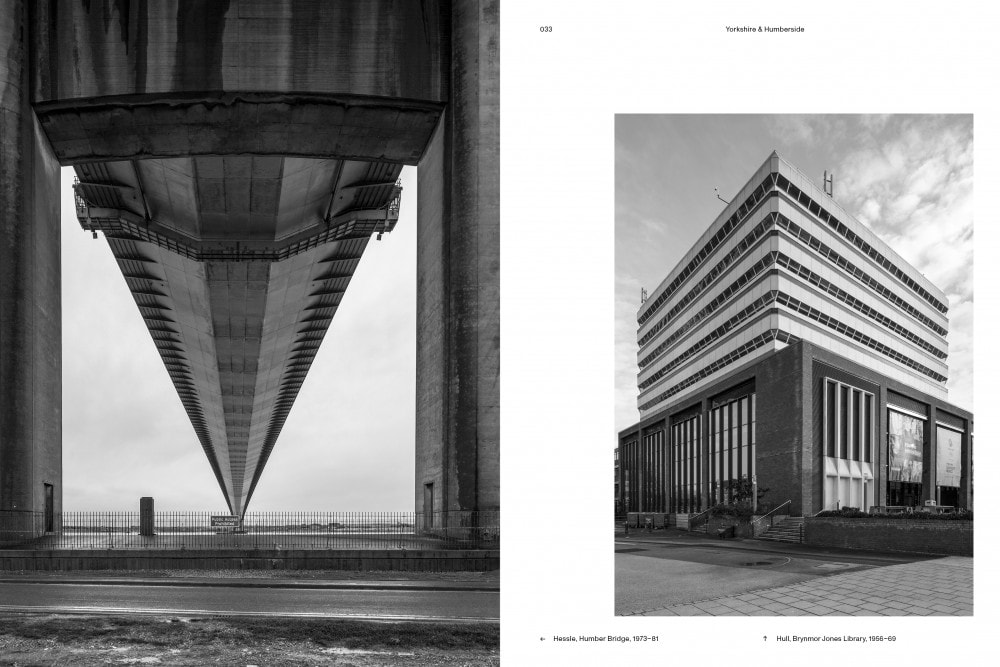

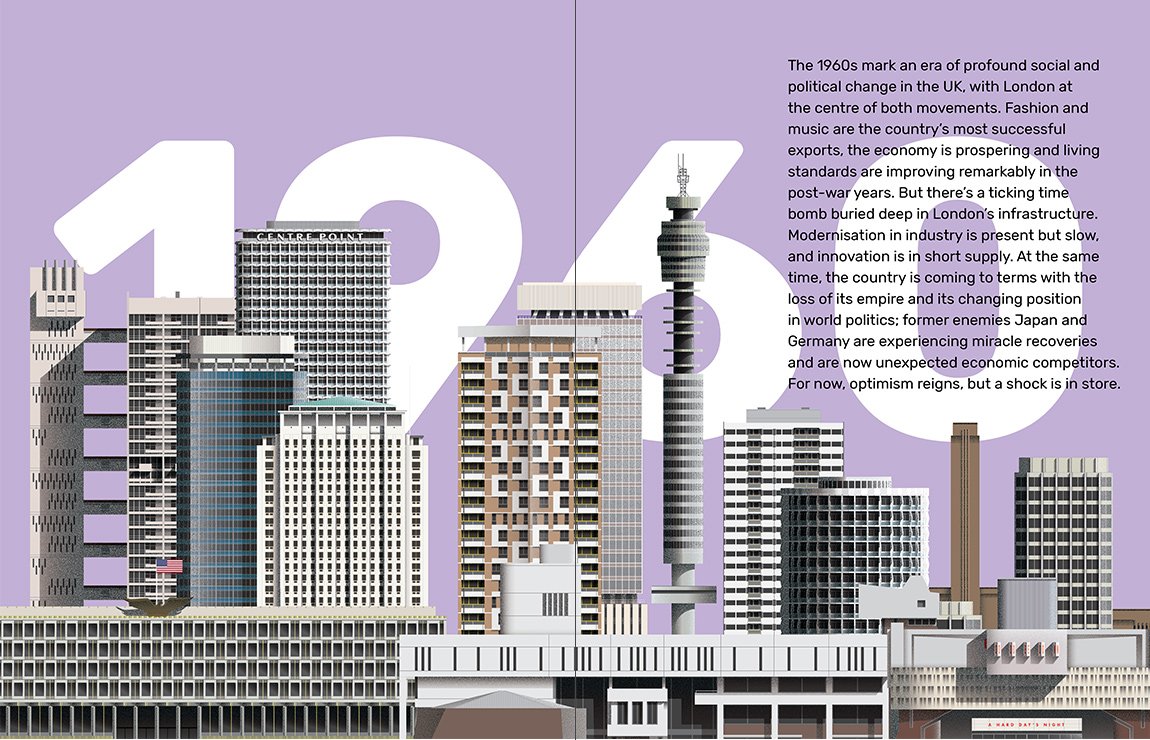

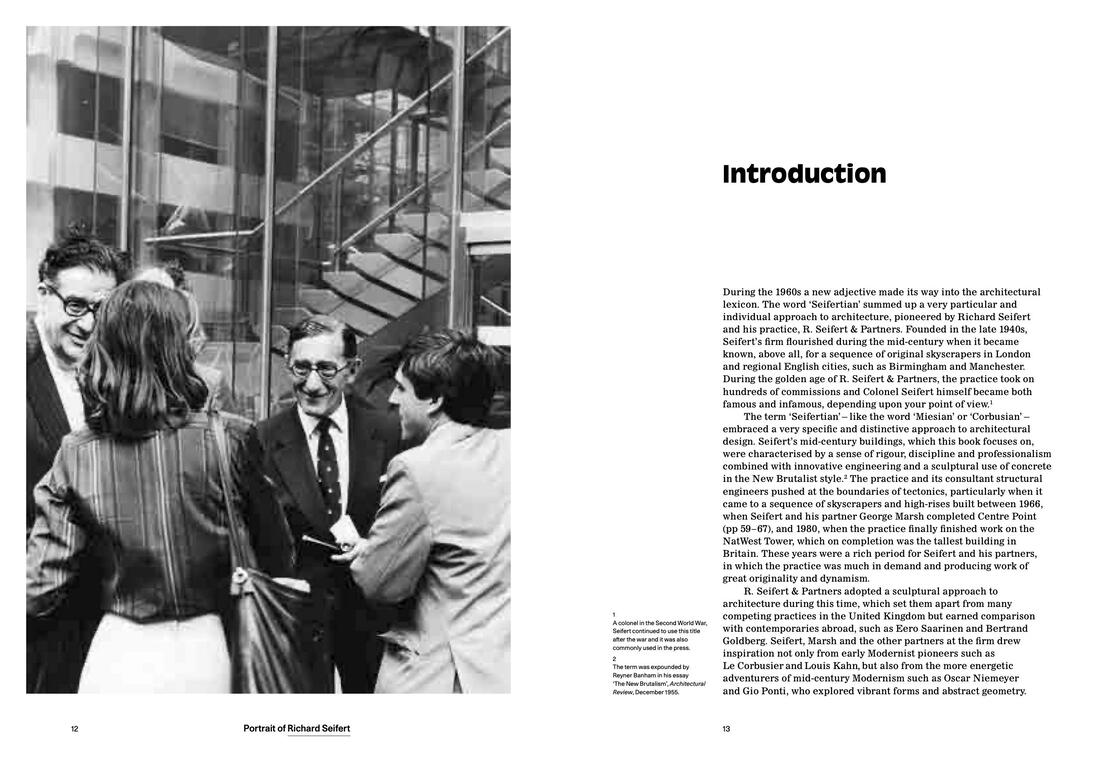

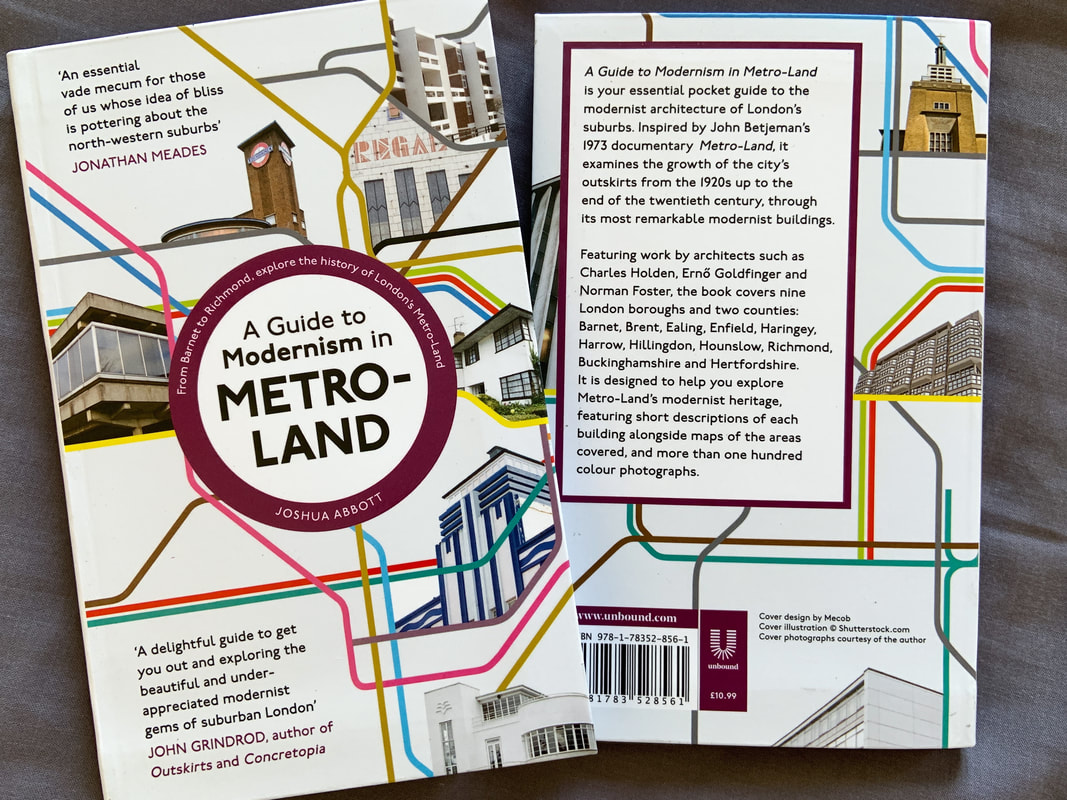

It's that time of year where we send our Christmas lists off to Santa, so we thought we would do a quick gift guide for the modernist at heart. Most of the books featured were published this year, but we have also included a few from 2019 that we missed at the time. First up is Luke Agbaimoni’s The Tube Mapper Project, a wonderful photographic journey around the tube network, capturing the hidden beauty of the underground world we all travel through but seldom notice. The project takes in Underground, Overground and DLR stations, and features poetry inspired by the tube and the city it serves. Luke also has Tube Mapper 2021 calendars available, both book and calendars can be purchased HERE Mark Amies is a writer and broadcaster who is a regular feature on Robert Elms BBC London Radio show. Out of his appearances grew London’s Industrial Past, an exploration of the factories that were once the backbone of the capitals manufacturing industry. In the first half of the 20th century every neighbourhood had a factory, producing everything from biscuits to aircraft. Featuring archive images and illustrations, it's the perfect gift for the local history enthusiast. The book is available HERE Moving northwards, Brutal North: Post War Architecture in the North of England is the new book from Simon Phipps, the man behind the Brutal London and Concrete Poetry books. The book focuses on the post war concrete buildings of the north, with buildings such as the Park Hill Estate in Sheffield and Preston Bus Station shown in all their glory through Simon’s powerful monochrome imagery. The book can be bought HERE Lukas Novotny published the excellent Modern London book last year, illustrating the capital architecture from the 1920s right through to the present day. Lukas also has a range of gifts available, from christmas cards to bookmarks to illustrations, perfect for the design buff in your life (even if that's you). All of them can be found HERE If you want to explore some Modernist neighbourhoods (more of which later..). Stefi Orazi has been producing a set of walking guides over the last 6 months, covering the best places to wander and see some of the best modernist architecture. So far, the guides cover Highgate, Hampstead, Archway & Belsize Park, Brussels, Blackheath and Bloomsbury to Barbican via Barnsbury. The guides are available individually or as a set which can be gift wrapped). Get them, and much more from Stefi’s site HERE If you like maps and want something further afield, Blue Crow Media have you covered. Their architecture and design maps take in everywhere from Chicgao to Tbilisi, via our own capital. You can see the full selection HERE. For the post war architectural devotee, two books published this year may be of interest. Richard Seifert: British Brutalist Architect by Dominic Bardbury chronicles the career of Seifert and explores 12 of his most famous buildings from Centre Point to the Natwest Tower. The other book is The Architectural Association in the Post War Years by Patrick Zamarian, an exploration on the role of the Architectural Association in the forming of post war architecture in Britain. Architects such as Neave Brown, Richard Rogers, Ted Cullinan, Nicholas Grimshaw, and nany, many more attanted or taught there, making it a crucible of design and ideas. If you want to get the architecturally minded in your circle something truly important, then what could be better than membership to the 20th Century Society? The C20 have been dedicated to saving, publicizing and exploring the buildings and design of 20th Century Britain and beyond. Becoming a member means you will relieve the C20 Magazine a few times a year plus their annualish C20 Journal, discounts on a range of talks and tours, and most importantly the knowledge that your money is helping preserve the architecture you love. You can also purchase their book 100 20th-Century Gardens and Landscapes, featuring a contribution from yours truly! Of course we can’t end with mentioning our own Guide to Modernism in Metro-Land. If you haven't got it already, we think it is the essential guidebook to discovering the modernist treasures of London’s suburbs. Featuring chapters on 9 London Boroughs and 2 counties plus maps, descriptions of each building and colour photographs. You can get your copy HERE. Whatever you get and give, we hope you all have a happy and safe Christmas!

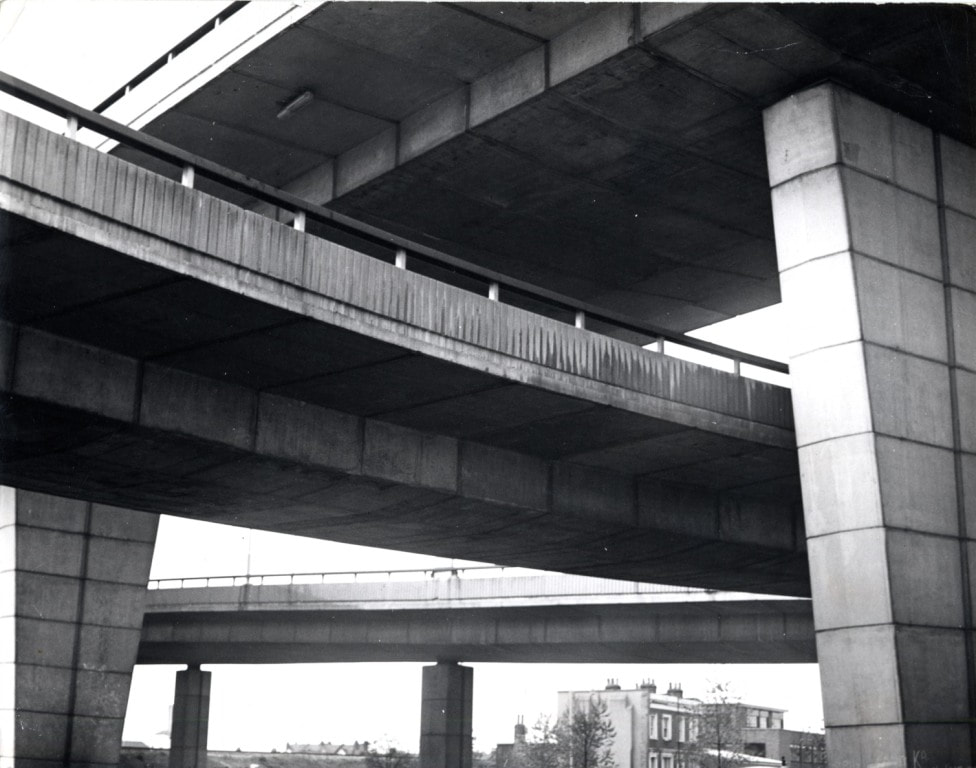

All these books, plus a few others, can be seen on our Bookshop.org page HERE J.G. Ballard was born on 15th November 1930 in the Shanghai International Settlement, where his father was managing director of a subsidiary of Calico Printers Association, a Manchester textile company. Following the outbreak of war and his internment, the basis of his book Empire of the Sun, Ballard and his mother and sister returned to Britain, where he studied medicine. After a spell in the RAF, Ballard took up his writing career, starting off selling short science fiction stories to magazines like New Worlds and Science Fantasy, before publishing his first novel in 1961. Ballards output of short stories and novels, which ranged from 1961 until his death in 2009, continuously tackles the problems of architecture and the built environment, with his protagonist often cast as architects and frequent mentions of Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright in his early short stories. His most famous work that tackles architecture is the 1975 novel High Rise, whose main character is the titular building, where civilization crumbles as the architect sits in his penthouse flat. The building in High Rise was said to be influenced by the Barbican Estate by Chamberlin, Powell & Bon, and the architect character, Antony Royal, supposedly based on Erno Goldfinger. “I came to live in Shepperton in 1960. I thought: the future isn't in the metropolitan areas of London. I want to go out to the new suburbs, near the film studios. This was the England I wanted to write about, because this was the new world that was emerging.” We won’t analyze High Rise or any of Ballards work here, but we will explore some of the buildings that were part of his life or that he admired. Ballard famously lived in suburban Shepperton, where he worked and looked after his three children after his wife Mary died in 1964. The house he lived in, 36 Old Charlton Road, is a typical 1930s sun trap suburban house. The sun trap styled house was developed by the practice of Welch, Cachemaille-Day & Lander, who produced houses designs for building companies like Haymills and Roger Malcolm, and it rapidly became the default suburban house design from the start of the 1930s. The design of the house itself combined streamlined metal framed windows (the sun trap), patterned tiling, stained glass windows and sunken doorways. Some of the houses had flat roofs, but most, like Ballard's, were pitched. The fact that Ballard lived in such a normal suburban house was a point of fascination with critics, as if a master of such dystopian writing could only live in an abandoned electric substation or indeed a high rise block. The Westway is an elevated dual carriageway which takes the A40 trunk road from west to central London. Construction began in September 1966 and it was opened in July 1970. It was designed by the Greater London Council Architects Department with engineering by G. Maunsell & Partners. The roadway is 2.5miles long and was conceived as part of the London Ringsway network, a ring road project that was never completed. The Westway features in two Ballard novels, Crash (1973) and Concrete Island (1974). The latter novel finds Robert Maitland, an architect, trapped in the intersecting roadway where again civilization breaks down amid concrete. Ballard would later call the Westway “like Angkor Wat... a stone dream that will never awake”. “Take a structure like a multi-storey car park, one of the most mysterious buildings ever built. Is it a model for some strange psychological state, some kind of vision glimpsed within its bizarre geometry? What effect does using these buildings have on us? Are the real myths of this century being written in terms of these huge unnoticed structures?” Ballard was frequently asked about his favourite building throughout his career, and his answers are fascinating and often in keeping with his obsessions. One of those was the car parks of Watford. Reports differ about which was his main inspiration between Church Road and Sutton car parks, but Ballard called Watford “the mecca of car parks” and made a short film, CRASH!, which would inspire his later novel. Three car parks were built in Watford between 1965 and 1970 as part of a transformation of the town centre. Car parks in Rosslyn Road, Church Road and Sutton Road were designed by B.L. Williams and F.C. Sage of the Borough Engineers Dept. with helix spiral ramps and rugged concrete construction. Car parks are a theme of his short story collection The Atrocity Exhibition, and he says in the short film CRASH! that he sees “multi story car parks and their canted floors as a depository for cars seemed to let one into a new dimension.” “I've decided to recast myself as Utopian. I like this landscape of the M25 and Heathrow. I like airfreight offices and rent-a-car bureaus. I like dual carriageways. When I see a CCTV camera, I know I'm safe”

Ballard would later say his favourite building was the Heathrow Hilton hotel. The Hilton, one of a cluster of hotels around Heathrow Airport, was designed by the firm of Michael Manser & Associates and opened in 1990 and later won awards from the RIBA and Civic Trust. Ballard said that it was a masterpiece and “keeps alive the spirit of the 20th century’s greatest architect, Le Corbusier. Beautifully proportioned, it resembles a cross between a brain surgery hospital and a space station”. Indeed Ballard seemed to have seen Heathrow as the real city centre, saying that Shepperton was a suburb of Heathrow rather than London. Though brutalist estates like Trellick Tower and the Barbican loom large in his work, we can see from the buildings that Ballard talked about in interviews, his obsession remained the car and all the structures associated with it; flyovers, underpasses, car parks and the roadside hotel. |

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed