|

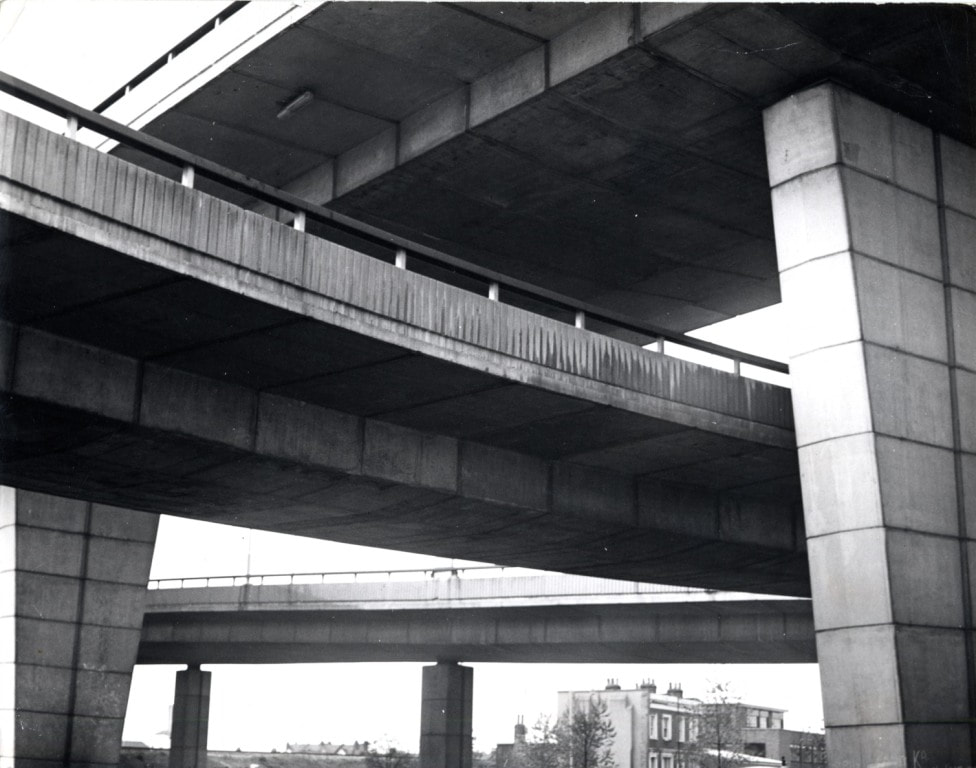

J.G. Ballard was born on 15th November 1930 in the Shanghai International Settlement, where his father was managing director of a subsidiary of Calico Printers Association, a Manchester textile company. Following the outbreak of war and his internment, the basis of his book Empire of the Sun, Ballard and his mother and sister returned to Britain, where he studied medicine. After a spell in the RAF, Ballard took up his writing career, starting off selling short science fiction stories to magazines like New Worlds and Science Fantasy, before publishing his first novel in 1961. Ballards output of short stories and novels, which ranged from 1961 until his death in 2009, continuously tackles the problems of architecture and the built environment, with his protagonist often cast as architects and frequent mentions of Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright in his early short stories. His most famous work that tackles architecture is the 1975 novel High Rise, whose main character is the titular building, where civilization crumbles as the architect sits in his penthouse flat. The building in High Rise was said to be influenced by the Barbican Estate by Chamberlin, Powell & Bon, and the architect character, Antony Royal, supposedly based on Erno Goldfinger. “I came to live in Shepperton in 1960. I thought: the future isn't in the metropolitan areas of London. I want to go out to the new suburbs, near the film studios. This was the England I wanted to write about, because this was the new world that was emerging.” We won’t analyze High Rise or any of Ballards work here, but we will explore some of the buildings that were part of his life or that he admired. Ballard famously lived in suburban Shepperton, where he worked and looked after his three children after his wife Mary died in 1964. The house he lived in, 36 Old Charlton Road, is a typical 1930s sun trap suburban house. The sun trap styled house was developed by the practice of Welch, Cachemaille-Day & Lander, who produced houses designs for building companies like Haymills and Roger Malcolm, and it rapidly became the default suburban house design from the start of the 1930s. The design of the house itself combined streamlined metal framed windows (the sun trap), patterned tiling, stained glass windows and sunken doorways. Some of the houses had flat roofs, but most, like Ballard's, were pitched. The fact that Ballard lived in such a normal suburban house was a point of fascination with critics, as if a master of such dystopian writing could only live in an abandoned electric substation or indeed a high rise block. The Westway is an elevated dual carriageway which takes the A40 trunk road from west to central London. Construction began in September 1966 and it was opened in July 1970. It was designed by the Greater London Council Architects Department with engineering by G. Maunsell & Partners. The roadway is 2.5miles long and was conceived as part of the London Ringsway network, a ring road project that was never completed. The Westway features in two Ballard novels, Crash (1973) and Concrete Island (1974). The latter novel finds Robert Maitland, an architect, trapped in the intersecting roadway where again civilization breaks down amid concrete. Ballard would later call the Westway “like Angkor Wat... a stone dream that will never awake”. “Take a structure like a multi-storey car park, one of the most mysterious buildings ever built. Is it a model for some strange psychological state, some kind of vision glimpsed within its bizarre geometry? What effect does using these buildings have on us? Are the real myths of this century being written in terms of these huge unnoticed structures?” Ballard was frequently asked about his favourite building throughout his career, and his answers are fascinating and often in keeping with his obsessions. One of those was the car parks of Watford. Reports differ about which was his main inspiration between Church Road and Sutton car parks, but Ballard called Watford “the mecca of car parks” and made a short film, CRASH!, which would inspire his later novel. Three car parks were built in Watford between 1965 and 1970 as part of a transformation of the town centre. Car parks in Rosslyn Road, Church Road and Sutton Road were designed by B.L. Williams and F.C. Sage of the Borough Engineers Dept. with helix spiral ramps and rugged concrete construction. Car parks are a theme of his short story collection The Atrocity Exhibition, and he says in the short film CRASH! that he sees “multi story car parks and their canted floors as a depository for cars seemed to let one into a new dimension.” “I've decided to recast myself as Utopian. I like this landscape of the M25 and Heathrow. I like airfreight offices and rent-a-car bureaus. I like dual carriageways. When I see a CCTV camera, I know I'm safe”

Ballard would later say his favourite building was the Heathrow Hilton hotel. The Hilton, one of a cluster of hotels around Heathrow Airport, was designed by the firm of Michael Manser & Associates and opened in 1990 and later won awards from the RIBA and Civic Trust. Ballard said that it was a masterpiece and “keeps alive the spirit of the 20th century’s greatest architect, Le Corbusier. Beautifully proportioned, it resembles a cross between a brain surgery hospital and a space station”. Indeed Ballard seemed to have seen Heathrow as the real city centre, saying that Shepperton was a suburb of Heathrow rather than London. Though brutalist estates like Trellick Tower and the Barbican loom large in his work, we can see from the buildings that Ballard talked about in interviews, his obsession remained the car and all the structures associated with it; flyovers, underpasses, car parks and the roadside hotel.

2 Comments

Hugh Pearman

16/11/2020 01:01:15 pm

Tiniest of typos - it's Chamberlin Powell and Bon, not Chamberlain.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed