|

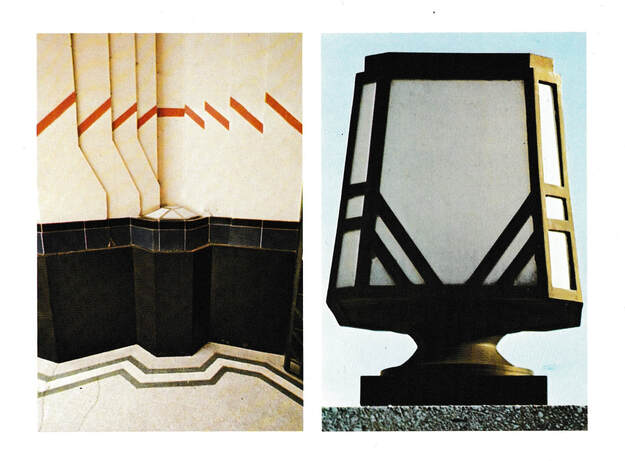

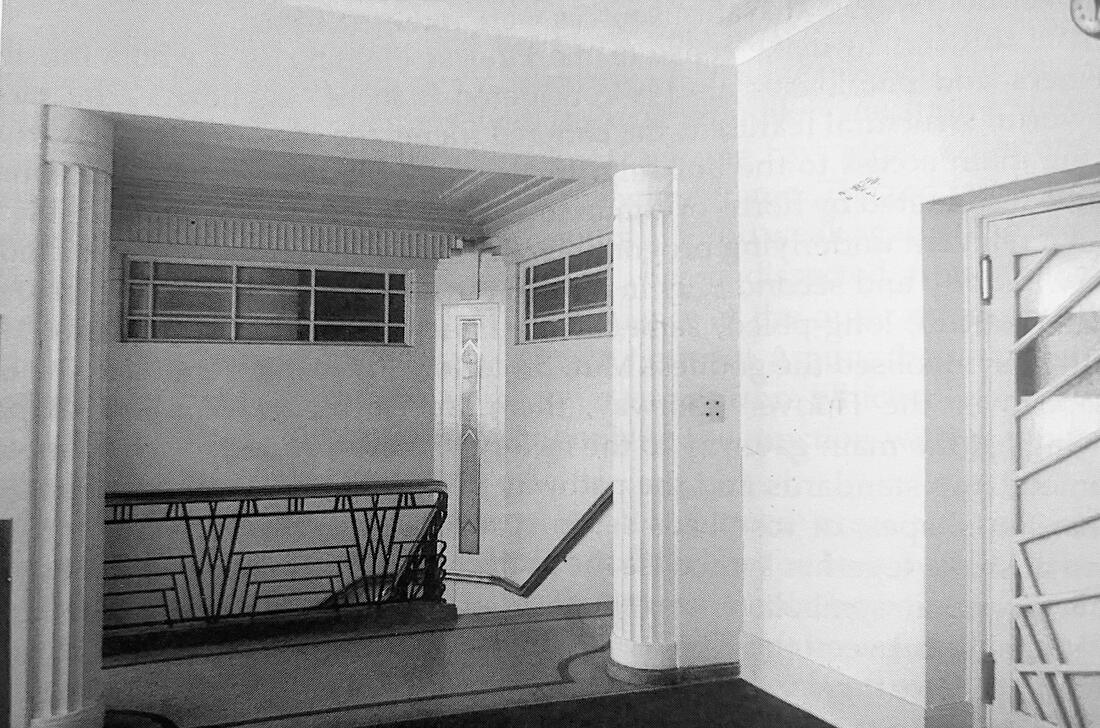

The Hoover Factory in Perivale, Ealing was officially opened on May 2nd 1933. Designed by the firm of Wallis, Gilbert & Partners, already well known at that time for their factory buildings on the ‘Golden Mile’ in Brentford, it has become a welcome landmark to many motorists and passengers along Western Avenue. Ten separate buildings were completed between 1932 and 1938 for Hoover, the ones facing the road ornate in their decoration, the ones hidden away much less so. The building has divided critics over the years with Nikolas Pevsner famously calling it “ perhaps the most offensive of the modernistic atrocities along this road typical of the by-pass factories”. Nevertheless the Hoover building was listed in October 1980, only months after its predecessor, the Firestone Factory in Brentford, had been demolished. The Hoover company originated in Ohio, originally dealing in harness and leather goods. A suction cleaner was developed in 1907, and became the companies central focus when the decline in horse transport affected their other product lines. A small manufacturing premises in London was established in the 1920s, but within a few years a bigger factory was needed. A site on Western Avenue was chosen due to its road and rail links with London and the rest of the country, and also due to the availability of housing for its workers. The company desired an eye-catching building along the main road, and Wallis, Gilbert & Partners were already well known for working with American companies like Firestone as well as producing buildings that made heads turn. The design of the first part of the scheme was overseen by architect Frederick Button, including the main office block facing Western Avenue. The block was designed in 1931, and stretches for 220 ft along the road, finished in generous glazing and decorated in coloured tiles. At either end are two staircase towers with quarter moon windows inspired by the work of Erich Mendelsohn. The main entrance doorway is spectacular, a riot of colour and patterns, designed to impress visitors and passers-by alike. The workers at the factory did not use this entrance, instead using the more circumspect door on the west side. The decoration of the main block is largely informed by ancient Egyptian motifs, popular since the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb by Howard Carter in 1922. References to various deities, including Amun and Mut, are used, as well as Horus-eye shaped paving. Some people have seen North and Central American influences in the decoration, and linked it to Hoover’s origin in the Midwest of America, but no documentation of this has been found. Visitors and the directors using the main entrance would be guided up a sweeping staircase decorated by a metal representation of the fan motif used on the exterior, to a waiting area painted in more neutral colours. A third floor and extensions were added to the main block in 1935, with more office space provided, and a couple of years later the canteen was moved to a separate building, designed by chief assistant John W. Macgregor. This can be found to the left hand side of the main block when facing it. The three storey canteen and garage block is constructed of reinforced concrete, and features a long vertical v-shaped window at the front, curved steel windows and a small deco clock. The Hoover factory did not just advertise its wares to the road in front, but also to the train line at the rear with a neon sign of the slogan “Beats as it sweeps as it cleans”. The building was also used in posters and adverts for the Hoover brand. Thomas Wallis was quite honest about the commercial aspect of his designs, telling the RIBA in 1933 that “ A little money spent on something to focus the attention of the public is not money wasted but a good advertisement”. The factory became part of popular culture with Elvis Costello writing and releasing a song about the building in 1980. After Hoover left in the 1980’s, Tesco took over the buildings, converting the rear into a supermarket and letting out offices in the front. The main block has now been converted into apartments. A planning dispute flared up in 2019, when developers submitted plans to build a 22 storey residential building right behind the factory. Significant opposition objected to the plan, and eventually a new proposal with reduced height was passed.

0 Comments

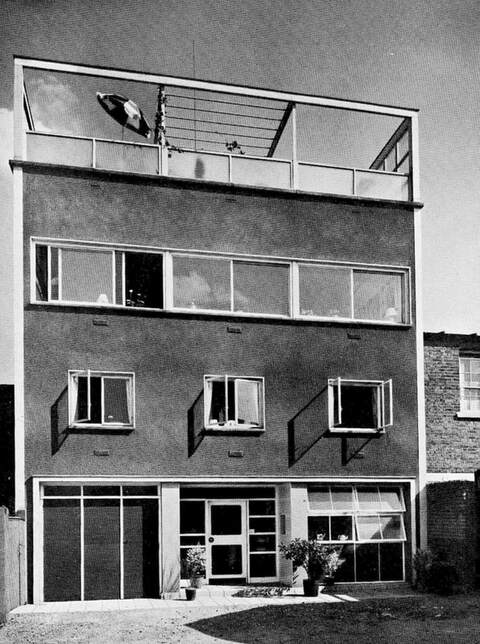

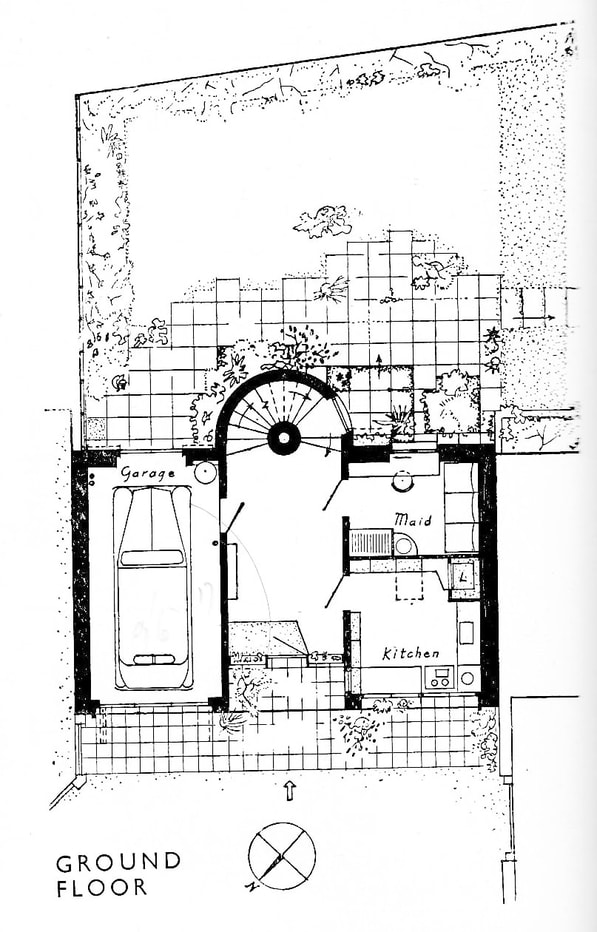

Anatomy of a House No.9 |

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed