|

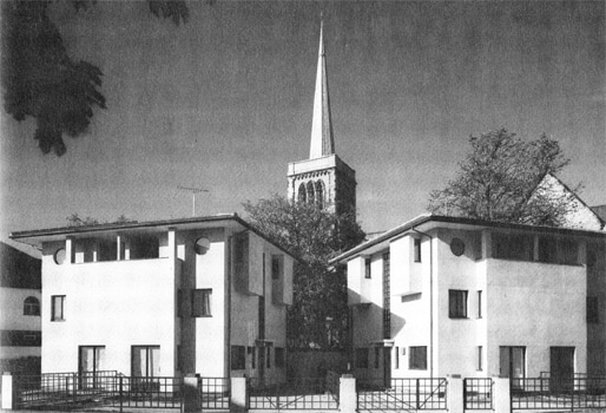

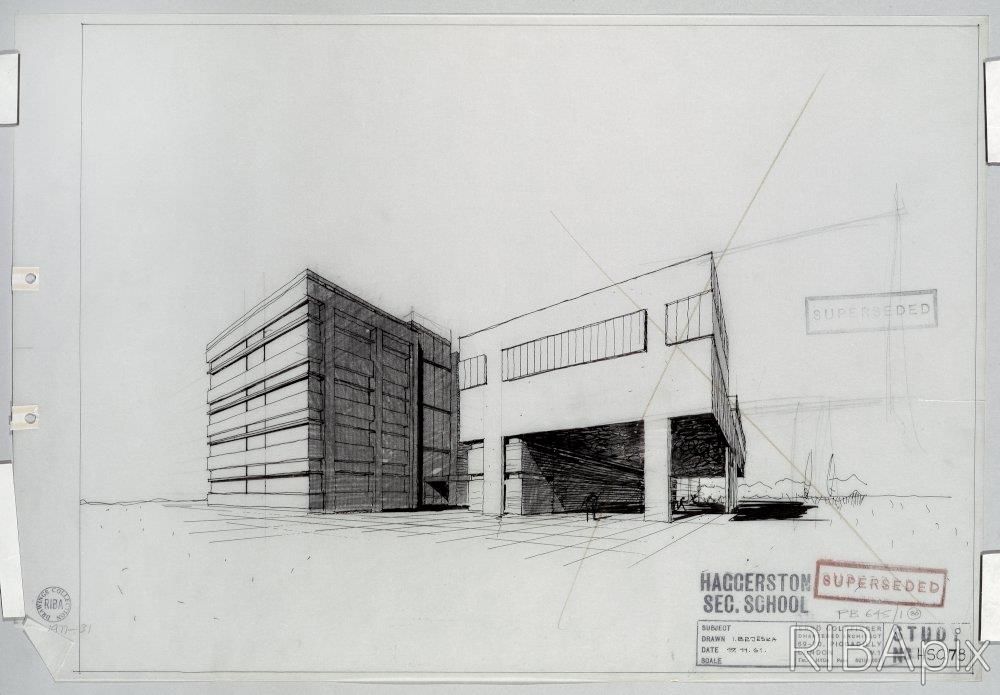

Two years ago, to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the founding of the London boroughs, we wrote a series of blogs looking at the work of the various boroughs architects departments. Over three parts we looked at the work of Camden, Haringey, Hillingdon, Hounslow, Brent, Harrow, Barnet and Enfield. We have decided to follow this series up and look at the work of Islington (Part 4), Hackney and Hammersmith (Part 5). This is a general overview, looking at some of the project each borough undertook as well as looking at the different approaches used. Part 1- Camden can be found HERE, Part 2- Hillingdon, Hounslow, Harrow & Brent can be found HERE. Part 3- Haringey, Enfield & Barnet can be found HERE. Part 4-Islington can be found HERE. Hammersmith & Fulham The creation of the borough of Hammersmith and Fulham in 1965 reunited two boroughs which had previously been part of the parish of Fulham. Both metropolitan boroughs had built housing estates before the 1965 merger. The LCC had built the Old Oak Estate from 1911 onwards, the Wormholt Estate from 1919, and the White City Estate on the grounds of the 1908 Olympic Games from 1938. Immediately before the 1965 reorganisation of boroughs, the Hammersmith Architects Department completed the Edward Woods Estate, featuring four 21 storey tower blocks mixed with maisonettes. The Fulham architect's department also built a number of estates in the borough in the period between 1945-65. The most interesting was designed by the borough architect, J. Pritchard Lovell, the Clement Attlee Estate was begun in 1955 and features three Y shaped point blocks, with one block featuring a library, as well as peaked roofs on the water tanks. After becoming Hammersmith & Fulham in 1965 (although called the London Borough of Hammersmith until 1979), the boroughs architects department built a number of estates in the contemporary systems built fashion. The West Kensington Estate built on the West Kensington Goods Yard site from 1970, contained nearly 400 dwellings. The estate was built by Gleeson Industrialised Building Ltd and consists of three brick clad tower blocks and a number of smaller maisonette terraces. Two slightly later and more interesting schemes are the King St Development at Ashcroft Square (1973) and Eternit Wharf in Stevenage Road (1976). King St is a nine storey high, rectangular shaped block that overlooks an internal courtyard garden. It is built in brick with concrete balconies, and is sited above a shopping centre designed by Richard Seifert & Partners. The scheme also features the Lyric Theatre, a recreation of the original 1895 building by Frank Matcham, which was recreated after a long campaign to save it. Eternit Walk in Fulham is a six storey block containing 20 dwellings and sports centre. It is designed in dark brick with stepped terraces, somewhat in the style of Darbourne & Darke. Darbourne & Darke themselves did work for the borough, designing part of the White City redevelopment, with four storey terraces in brick (1975-8). Nearby is Malabar Court, an old people's homes designed in hexagonal form by Noel Moffett for the GLC. Other outside architects who designed schemes for the borough include Higgins, Ney & Partners who built two projects; the Moore Park redevelopment on the Fulham Road (1967) and the Reporton Road Estate (1968), both featuring deck access apartments. Renton Howard Wood Associates also low rise access deck housing at Masbro Road (1970) as the borough experimented with commissioning smaller scale projects. Later on the borough moved to the vernacular style pioneered by Hillingdon, projects on Banim St (1979) and Munden St (1981) reflect this. Away from housing, the borough produced some other notable projects. Local boy and future Lambeth chief architect, Edward Hollamby designed Hammersmith School while working for the borough in 1954. The school has separate boys and girls buildings with shared facilities. The buildings were designed in brick and timber, due to post war material shortages, and also feature decoration in tiles and William Morris wallpaper. Around the same time Erno Goldfinger designed Westville Road Primary School (now known as Greenside). It is only one of two primary schools the architect designed, and features a concrete frame and a mural by Gordon Cullen. A later school of interest is Hammersmith & West London College by Bob Giles for the GLC. It was planned from around 1965, but was only completed in 1980, and is built of the hard red brick that was so fashionable in the late 70’s and early 80’s.In 1971 the architects department built a five storey concrete extension, featuring a recessed mezzanine, to the interwar Town Hall, as well as an octagonal registry office a little to the south. Hackney The London borough of Hackney was formed from the municipal boroughs of Hackney, Shoreditch and Stoke Newington. The growth of this area in the late 19th century led to the building of a number of estates by the LCC, as well as housing trusts such as Guinness and Samuel Lewis. After the end of World War II, Frederick Gibberd designed a number of estates alongside G.L. Downing, the surveyor for Hackney. Shacklewell Road, Somerford (both 1947), The Beckers (1956) and Kingsgate (1961), all contain a mix of low and high rise housing, influenced by the Scandinavian form of modernism with pervaded Britain in the first 15 years of the post war period. A similarly influenced scheme was the LCC’s for the Woodberry Down estate, built from 1946 and planned by J.H. Forshaw. The estate was laid out in a Zeilenbau style; with the housing slabs arranged in parallel rows, allowing for light and green spaces in between. Robert Matthew, then the LCC’s chief architect, designed the buildings for the estate, which also included a school, library, health centre and shops. Another notable LCC estate in Hackney is the Bentham Road Estate. Built between 1956-9, and designed for the LCC by designers like Colin St John Wilson and Alan Colquhoun, Bentham Road was heavily influenced by Le Corbusier and was one of the first British estates to be built of reinforced concrete. The first estates of the post-1965 architects department tended to the prevailing fashion for systems built tower block. Thaxted Court on Fairbank Street (1966-70) is a good example of this, a 20 storey block with 72 flats and a 6 storey block with 30 homes built by direct municipal labour, as many of the early Hackney estates were. Later, building contractors such as Fram, Higgs & Hill were bought in to build estates on a design and build contract, where the contractor would oversee the whole project from the drawing board to completion. The estates at Holly Street, Clapton Park and Kings Crescent were all built by Fram, Higgs & Hill in this way. It possibly says something about this way of working, that these three estates have all had significant alterations and demolitions since. Leonard Manasseh & Partners extended the Arden Estate in Hoxton, originally built in the 1950’s, for the GLC from 1968, adding four storey blocks with dramatic tiled refuse chutes. The firm of YRM, built the Kingshold Estate off King Edwards Road in 1972. It featured two 23 storey blocks, five 5 storey blocks and 2 terraces of houses, making up nearly 800 homes. The estate was constructed of concrete units cast at an on site factory. Despite winning a Concrete Society award, the estate was demolished in 1996. Two later housing projects in Hackney show new approaches being tried by the borough. The Primary Support Structures and Housing Assembly Kit (PSSHAK) was developed by Nabeel Hamdi and Nick Wilkinson as students and they bought it with them when working for the GLC. PSSHAK allowed housing schemes to be designed and built with flexible elements meaning designs could be altered even after construction had begun. The first PSSHAK was built in Stamford Hill in 1976, and although the idea did not spread the buildings are still in use. Colquhoun and Miller, who had previously worked for Haringey, built two sets of houses for the borough at Church Crescent and Brownlow Road (both 1984). The Church Crescent homes are a pair of white rendered semi detached houses with CR Mackintosh inspired windows and overhanging inset balconies. The Brownlow Road, (also on Albion Road), houses have shared pediments with recessed porches and were designed to be in keeping with their 19th-century neighbours. Away from housing, the borough built a number of interesting buildings. Stamford Hill Library (1968) has a two storey front with stone floor bands in white and blue, Homerton Library (1970) is again two storey with a brick faced frame, and the Rose Lipman Library & Community Centre (1967) is a brick and glass structure next to the De Beauvoir estate. The borough has a few interesting schools, including Erno Goldfinger’s Haggerston Girls School (1962-7), designed for the LCC. Another brutalist style Secondary school in the borough is Stoke Newington School (originally called Clissold School) designed by Stillman & Eastwick-Field and completed in 1970. Its most distinctive feature is the see through boiler room, now converted into a Sixth Form Centre. Also designed for the GLC was Bethnal Primary School by Paul Maas. The school consists of eight individual linked buildings, rendered white and with curving roofs, giving the impression of a collection of tents. YRM built an 8 storey flatted factory building on Ada Street (1966). This building replaced workshops demolished in creating new estates, and aimed to separate housing and industry. Other flatted factories were built in Hackney on Richmond Road (1959, Leslie Creed) and Long Lane (LCC, 1958). A final set of buildings to note are Hackney’s fire stations. Designed by the LCC and GLC Special Works department, led by Geoffrey Horsfall. Shoreditch (1964), Homerton (1972), Stoke Newington (1974) and Kingsland (1975) station were all built in an uncompromising brutalist fashion, with combinations of exposed concrete frames, cantilevered windows and concrete blockwork.

2 Comments

|

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed