|

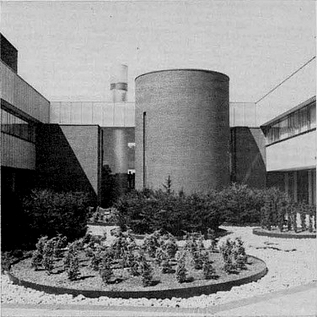

In the first two parts of this series we saw how some of the Metro-Land boroughs responded to their new powers post 1965. Camden and Hillingdon executed wide ranging programmes of low rise social housing, using modernism and the neo-vernacular respectively. Other boroughs, such as Hounslow and Brent, stuck to the contemporary high rise, prefab of the era. In the final part we will see how the architects departments of the North Eastern boroughs went about their business. We will be looking at the buildings of Haringey, Enfield and Barnet. Haringey Haringey probably stuck the closest to Sydney Cook and Camden’s blueprint of progressive, low rise housing designed by a variety of in house and private architects. Like many of London's boroughs, Haringey encompasses both the rich and poor, taking in the middle class villages of Highgate and Hornsey, as well as the deprived areas of Wood Green and Tottenham. The former area was well served by private development, so the borough concentrated their efforts on the latter. The borough's flagship project was the Broadwater Farm Estate (1966-71) in Tottenham. Overseen by chief architect C.E. Jacob and deputy Alan Weitzel, it was designed to house between 3,000-4,00 people in just over 1000 homes. The estate consists of 12 buildings connected by walkways, in a mix of high and low rise. They were constructed using plain concrete slabs in a system built plan. The architectural centrepiece is Tangmere, a six storey ziggurat, combing shops and homes, with angled balconies. The estate became infamous during the riots of 1985 and murder of PC Keith Blakelock. Following this, a regeneration plan was implemented, and over the next 30 years the estate was refurbished, leading to it having some of the lowest urban crime rates in the world and a lengthy waiting list to move onto the estate. Haringey mirrored Camden in utilising a mixture of in house and private architects design housing projects. Of their in house staff,one of the most prolific was Bertram Dinnage. Dinnage designed a variety of projects during his time at the borough including libraries (Wood Green,1978), health centres (Crouch End, 1984), housing (Chesnut Estate, 1971 & Pelham Court, 1979) and an education centre for the TUC (1983). Other architects who worked for the borough include Janina Chodakowska who designed a small estate of terraced houses and flats at Grovelands (1971) by the River Lea, and A.Maestranzi who designed the Suffolk Road Estate, a scheme of timber framed brick homes, with monopitch roofs. Like Camden, Haringey brought in many young private architects to provide them with smaller housing schemes. Colquhoun and Miller, whose work for Camden we saw in Part 1, designed a number of projects, the most interesting of which is The Red House home for the elderly in Wood Green. Completed in 1976 in orange brick, the building is neatly fitted onto an awkward triangular site. The duo also designed Garton House (1980) a nine storey block for single people on Hornsey Lane, as well as a couple of minimalist community centres on the Chesunt and Suffolk Road estates. The firm of Douglas Stephen & Partners designed houses in Penrith Road & Appleby Close (1975) and a health centre in Bounds Green (1978). Ivor Smith (who helped design the Park Hill flats in Sheffield) and Cailey Hutton designed Morant Place (1975), two long ziggurats that face each other, just off Wood Green High Road. A couple of other interesting projects by outside architects are Colin St John Wilson & Partners low rise housing on Daleview Road (1974), and Lee, Quine and Miles’ housing for the elderly in Roseland Close and Larkspur Close (1973). Another project for the borough was landscape architects Mary Mitchell’s childrens playground created out of the ruins of Victorian industrial buildings on Markfield Road (1966). Mitchell’s playground is no longer there, but it is still a recreation park. Enfield Enfield was formed from the municipal boroughs of Southgate, Enfield and Edmonton. It was in Edmonton’s architects department that the new borough found its first chief architect. T.A. Wilkinson. As chief architect of Edmonton, Wilkinson had experimented with the prefab building system, BRECAST, which was developed by Nares Craig at the Building Research Unit in Garston. Wilkinson used the system to build Angel House, Edmonton (1964) using Edmonton’s Direct Labour Organisation, a facet he would also use when in charge of Enfield. Wilkinson used the BRECAST system to built the Barbot Estate (1968), a scheme of 4 23 storey towers with chequerboard cladding. The estate was demolished in 2002, and replaced by low rise housing. Plans had been drawn up by Frederick Gibberd for the redevelopment of the Edmonton Green area in 1960, incorporating shops, housing, car parking and a civic centre. After the 1965 reorganization these plans were curtailed, leaving Wilkinson's Leisure Centre the main focus of the area. A undecorated concrete box that housed a 25m pool, squash courts and a cafe, work begun in 1965 and was completed in 1972. The building has now been demolished and replaced by new leisure facilities. Another demolished building is Ordnance Road Library by N.C. Dowell. Built in 1976, the library was a dynamic composition in concrete, with upright concrete beams supporting a second floor that looked over the open plan ground floor. The building was demolished in 2012 to make way for a new health centre. One building that does survive is the Enfield Civic Centre on Silver Street, designed by Eric Broughton & Associates who also designed Harrow’s. The initial part of the design took place between 1957-61, with a long brick administration section in blue brick, with a projecting upper floor. The second phase is very different, consisting of 12 storey, stainless steel clad tower built adjacent to the first phase of the scheme. Barnet Just as Harrow and Brent benefited from their inheritance from the progressive Middlesex County Council, so Barnet enjoyed the fruits of the post war Herts County Council school building programme. With a wealth of new, innovative schools in the area, the borough concentrated on housing. Their big project was the Grahame Park Estate. Built on part of Hendon Aerodrome, the scheme was designed to house 10,000 people in a mixture of public and private housing. The estate also includes a library, a church, a community centre and shops. The project was planned jointly between the boroughs architects department and the GLC’s. The estate was designed in a contemporary modernist manner, with six and seven storey concrete framed apartment blocks finished in dark brick. Construction began in 1969, and was completed by the end of the 1970’s. In 1989, the Borough undertook a remodelling and regeneration of the site. The austere buildings were softened by adding pitched roofs and red railings and window frames. The interconnecting walkways were also removed from between the blocks. The estate is currently being regenerated by the borough with new blocks being built and the old buildings being gradually demolished. Just to the east lies the lesser known Grahame Park West, also built by Barnet Borough and the GLC. This estate, now known as Willow Gardens, is a low rise scheme of houses and maisonettes in brick with wood cladding. Work on the site began in 1971, completing in 1975. Willow Gardens is not part of the Grahame Park regeneration plan. Another housing development built by the borough was Strawberry Vale (1975), designed by the firm of Bickerdike Allen Bramble. The firm were presumably chosen as they are experts in environmental acoustics, and the site for this estate is right next to the North Circular. The finished design consists of a long curving barrier block of five storeys, protecting the estate from the noise of the traffic (much like the Alexandra Estate in Camden), with monopitch brick houses clustered in the centre. The other type of building Barnet had success in designing was libraries. B.Bancroft designed the L-shaped Hale Lane Library in 1961 as chief assistant at Hendon Borough, and when he became Barnet borough architect post-1965, he designed Burnt Oak Library in 1968. The two storey library was constructed around a concrete frame with narrow vertical windows and a glass pyramid roof light. The building was refurbished by Knott Architects in 2011. Over the three parts of this series, we have seen the differing ways the new boroughs responded to their building needs. Camden, Hillingdon and Haringey introduced innovative methods and building types, using a variety of young in house and outside designers. Hounslow, Barnet and Enfield initially used system built large estates, but changed as the 1970’s started, using brutalist expressionism and brick, low rise buildings to vary their approach. Harrow and Brent largely stuck to the tried and tested highrise, prefab estates that form post war architecture in the popular imagination. The success or otherwise of these various approaches can perhaps be measured by whether the fruits of these approaches are still intact. In the first group, most of the buildings are still being used for their intended purpose, with many listed in Camden's case. In the second group some still survive, but even these are being redeveloped, and for the last group it seems there will be very little left soon to remember their work. In an age where council built housing of any stripe is rare, it is good to remember the different approaches employed by the boroughs, and their success and failures, in the post 1965 period.

References- The Buildings of England- London 4: North by Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner

1 Comment

As I tweeted last week, this year I have been asked to host an Open House London tour. On Saturday 19th September I will be guiding two walking tours, looking at Stanmore's Interwar and Post War houses. Beginning on the Warren Estate, featuring a host of interwar Art Deco and Streamline Moderne houses by Gerard Lacoste and Douglas Wood Architects, the walking tours will also explore other dwellings by the likes of RH Uren, Owen Williams, Gerard Kaufman, Rudolf Frankel and others. We will see how the expansion of rail and road links fuelled the rise of Metro-Land, and how architects bought modernism to sit amongst the prevalent suburban tudorbeathen style. The Open House London page for the tour is HERE. If you have any questions please feel free to email me at [email protected]

IMPORTANT INFO: The tours will be on Saturday 19th September ONLY. There will be a two tours, the first at 10am, the second at 2pm. The tours require no booking, but are on a first come basis, up to a maximum of 25 people. The meeting place for the tours will be opposite Stanmore Tube station. The tours will last between 1.5-2 hours and will include a steep climb at points, please bring protective clothing and suitable footwear. To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the creation of the London boroughs in 1965, we will be taking a three part look at the work of some of the boroughs Architects Departments that made up Metro-Land. In Part 1 we took a look at the work of Camden under Sydney Cook, and its subsequent golden age of social housing under a variety of architects. In the remaining 2 parts we will see how the other boroughs in north London responded to Camden’s lead in differing ways. In House Part 2: Hillingdon, Hounslow, Harrow and Brent. In this part we will look at the work of the Architects Departments for the north west boroughs; Hillingdon, Hounslow, Harrow and Brent, and see that they produced very different responses to providing social housing and building. Hillingdon provided a response that was in some ways very different from Camdens, and yet shared many of the same traits. Under chief architect Thurston Williams (1924-85), Hillingdon eschewed the white walled concrete appearance of Camden's estates. Instead they used smaller developments, usually in brick ,with pitched roofs. Like Camden, Hillingdons developments tended to be low rise, and with ground level entrances. The flagship for their Neo-Vernacular style was the Hillingdon Civic Centre in Uxbridge (1977) by RMJM. The building was unlike any civic centre building in the post war period, replacing concrete uniformity was red brick, pitched roofs nd an irregular frontage. Internally the usual warren of small offices was replaced by open plan spaces arranged in four quadrants. The Alfred Beck Leisure Centre echoed the Civic Centre in its rejection of concrete modernity for irregular frontages and multiple rooflines. The experimentation extended to not only the design of buildings, but the type they produced. Hillingdon provided accommodation for single people, community homes and expandable houses. Williams himself designed the St Christopher's Community Home in Hayes (1973). An arrangement of linked two storey houses in yellow brick with mono pitched roofs built for teenage boys as an alternative to borstal. The building was demolished and replaced with a Mcdonalds at the end of the 1990’s.In Whitehall Road the borough built a complex for single people, Colley House (1977), one of the first in the country to do so. In Harefield, the Borough experimented with expandable houses. Whilst they look fairly ordinary on the outside, the houses in and around Hinkley Close (1976) were designed by Brian Wood to be easily expanded by adding extra rooms on the top floor. Just as Camden bought in outside architects to keep their projects innovative, so did Hillingdon. The duo of Graham Shankland and Oliver Cox designed a number of schemes for the borough like Lych Gate Walk (1974) built on the site of the Hayes Court country house This scheme used different finishes, as well as different window size and roof height, for each house in a terrace to create a organic village feel. Shankland Cox produced similar small schemes for Hillingdon at Braybourne Close, Uxbridge and Hobart Lane and Raeburn Road, Hayes (all 1978). The firm of Douglas Stephens & Partners designed two high tech influenced libraries at Oak Farm (1976) and South Ruislip (1970,now demolished). Perhaps the most interesting collaboration was Edward Cullinan Architects Highgrove Estate (1977) at Eastcote. Built in the grounds of Highgrove House, this estate of terraced houses are arranged in back to back clusters, enlivened by blue, sloping roofs and wide frontages. In contrast to Hillingdon, the other three north eastern boroughs would stick more to the status quo of mid-60’s municipal building. Hounslow, under former LCC schools architect GA Trevett, used the system built concrete style to provide most of their construction needs. The Haverfield Estate in Brentford was built in two phases. The first phase completed in 1971, saw the construction of 6 23 storey blocks, with the second phase, adding houses and smaller blocks of flats, went from 1974-79. This estate was constructed using the prefabricated concrete panels so common at the time, and fared as well as its contemporaries, with the estate becoming run down and crime ridden by the mid 1980’s. Trevett was also responsible for the design of the brutalist style Heathlands School (1972), just off Hounslow Heath. However the thick concrete walls had a practical use in this case, protecting the pupils against the noise pollution of nearby Heathrow Airport. The borough was capable of producing more subtle designs, as seen at Nantley House (1969), a one storey nursery in yellow brick in a hexagonal plan. The borough also created a Civic Centre (1975), a long low structure made up of four pavilions where the concrete and brick materials are offset by the landscape design of designer Preben Jacobsen. One scheme by an outside architect for the borough is Lovat Walk (1977) by Edward Jones (later of Dixon Jones). An almshouse style group of sheltered accommodation around a courtyard with white walls and porthole windows, it makes a contrast to much of the boroughs other work, and nods to Hillingdon's mixing of styles. Despite the inheritance of the progressive Middlesex County Council example, who under Curtis & Burchett and then CG Stillman produced schools, clinics, libraries and more from the 1930’s onwards, the boroughs of Harrow and Brent did not not have an illustrious 1960’s and 70’s. Under the leadership of GJ Foxley, Harrow predominantly used the No Fines concrete system for residential buildings, for example at Dobbin Close, Belmont (1976) and Grange Farm (1968). The latter is due to be redeveloped. A more interesting housing development for the borough was designed by the firm of Howell Killick Partridge Amis at Stonegrove Gardens (1968) near Edgware. A development of maisonettes, flats, bungalows and a community hall, all in brick with long sloping roofs, and centered around a green. Foxley himself designed a similar scheme at Antoneys Close in Pinner (1972). Here there is no central green, but there is a mixture of bungalows with monopitch roofs for the elderly, as well as terraced houses for families. No borough was complete in the 70’s without a civic centre, and Harrow was no exception. Its Civic Centre on Station Road was designed by Eric Broughton (who also designed Enfield’s) and combines council offices, registry offices and a library in a six storey concrete building around a courtyard. As The Buildings of England- London 3: North West notes, “Since the mid C20, nothing of architectural consequence has been built in Brent”. The boroughs Chalkhill Estate (1966-70), situated opposite Clifford Strange's Town Hall (1940) was a typical post war systems built estate. Housing five thousand people in thirty linked apartment blocks as well as some low rise housing, it built using the Bison wall frame construction system. The estate did contain numerous facilities, like health clinics, shops, a police station and play areas, but the usual spiral of neglect made the estate notorious by the mid-1980’s. By the mid 1990’s the estate began to be demolished and has now been completely replaced by a new low rise, low density development. Two later estates in Stonebridge Park, St. Raphael of the late 1960’s and Dorman Walk of the 1970’s both survive, although both are due to be redeveloped as part of a borough wide scheme by Rick Mather Architects. One Brent estate that does get a positive mention in Pevsner is Everard Way, North Wembley (1980). Designed by Keith Morris, this low scheme of 139 homes shows a shift in attitude from the previous developments, with all front doors opening on to the street, in the mode of Camden and Hillingdon.

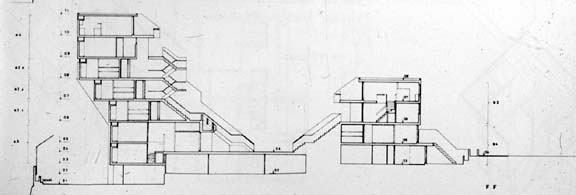

In part 3 we will see how the north east boroughs of Haringey, Enfield and Barnet used their post 1965 powers to provide social housing and more for their populations. To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the creation of the London boroughs in 1965, we will be taking a three part look at the work of some of the Architects Departments of the boroughs that made up Metro-Land. Starting with the most celebrated borough, Camden, we will also look over the legacies of Haringey, Hillingdon, Hounslow, Brent, Harrow, Barnet and Enfield. Pre-1965, the area most of these boroughs covered was administered by Middlesex County Council, and local borough councils. The pioneering work of Curtis and Burchett and CG Stillman for the MCC was carried on in the newly formed boroughs by the likes of Sydney Cook in Camden and Thurston Williams in Hillingdon. Every borough started out in the dominant Modernist ethos of the mid-60’s but by the middle of the next decade, a shift in styles had started away from tower blocks to smaller buildings and from Brutalism to Neo-Vernacular. As we look at the work of the boroughs mentioned above we will see the shifting taste and ideals of 25 years of architecture. Camden The in depth history the heroic age of social housing in Camden has been excellently covered elsewhere, by Municipal Dreams and Ruth Lang among others, so we wont go too in depth into the history of this era, but will present an overview of the architects and their buildings. Sydney Cook (1910-79) was Camden's first borough architect, and it was under his direction that the borough gained a reputation for producing progressive, experimental architecture designed by a group of young architects. Unlike many of the boroughs we will be looking at, Camden's modern architectural legacy came from the London County Council rather than the MCC, as well as progressive organizations like St Pancras Housing Association. Cook moved to Camden after leading Holborn Borough Architect's Department, and he encouraged an innovative, devolved approach to design among his architects. Cook emphasised the need to move away from tower blocks towards more traditional terraced structures, whilst using new construction techniques and finishes. To achieve this Cook used a number of young talented architects who were given space to realise their designs. Neave Brown was born in the United States and moved in London to study at the Architectural Association. His terrace of five houses in Winscombe Street (1965) for a small housing association of architects, including Michael and Patty Hopkins, would prove influential on his and others work for Camden, with each residence having a front door opening onto the street and access to a garden or sun deck. Hallmarks which would be incorporated into the borough's housing schemes. Brown produced two major projects for Camden; Dunboyne Road (1977) and the Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate (1978). The Dunboyne Estate (aka Fleet Road) was designed by Brown in 1966, and built in stages between 1971 and 1977. It contains 71 homes, in a mixture of 2 & 3 bed maisonettes and 1 bed flats in three parallel blocks, built with white washed concrete block, and wood finish for windows, doorways and balconies. The long stepped ranges face each other and have become abundant in foliage from the individual gardens. This same effect was repeated at Alexandra Road. Brown's plans for Alexandra Road were completed in 1968, with the estate again built in stages between 1972 and 1978. The site contains homes, a community centre, youth club and a school. The housing is arranged mainly in three long curved concrete ranges, with the south facing range Block A, protecting against noise from the neighbouring railway. There are 520 flats on the site, in a mixture of storeys and bedrooms. The site also features Ainsworth Way, comprising of three linked rows of three storey houses. The delays and overspend in completing the estate triggered a public enquiry, which led to Brown not designing any buildings in Britain for the rest of his career. However he still lives on the Dunboyne Estate, and both estates are listed. Sydney Cooks faith in young architects is exemplified by his use of Peter Tabori’s student project as the basis for the Highgate New Town project. Tabori had also assisted both Erno Goldfinger and Denys Lasdun, and so was well versed in modernist projects. The Hungarian born architect produced the plan for Highgate New Town as a project while a student at Regents Street Polytechnic. Cook was so impressed by the plan he asked Tabori to implement it when he joined the department. The scheme consists of stepped terraces, made of precast concrete panels and concrete floor slabs poured on site. The terraces are designed so each home has access to at least one south facing terrace or courtyard. The 273 homes that make up the site consist of flats. maisonettes and houses. As with Brown’s estates, construction of Highgate New Town began in 1972 and overran, eventually finishing in 1979. Tabori also designed Oakshott Court (1976) in Somers Town near Euston and St Pancras stations. Built on a square site, the building sitting in a L shape around a green space. The structure consists of stepped terraces containing 114 homes, made up of flats and maisonettes. Gordon Benson and Alan Forsyth joined Camden Architects Department in 1968, and worked with Brown on the Alexandra Road estate. They produced three important works for Camden, Mansfield Road and Lamble Street (1980), the Branch Hill Estate (1979) and the Maiden Lane Estate (1982). The Mansfield Rd/Lamble St project consists of 73 flats on Mansfield Road and 8 Houses on Lamble St, with construction starting in 1974 and only completed in 1980 due the complex technical demands the duo’s designs required. Their design for Branch Hill places 21 houses on a hidden, sloping site in Hampstead. The houses are constructed in concrete, with a whitewash finish and timber detailing, as on a number of other Camden projects. Once again the project was late and over budget, creating a media backlash. The Maiden Lane estate is considered the last project of Camden’s golden era. After a decade of renowned yet costly and late projects, this scheme just off York Way in the north of King's Cross was Camden's last hurrah. The scheme is made up of 225 dwellings, in a combination of flats, maisonettes and townhouses. The finished estate was alternately hailed as a model new community and as virtually uninhabitable. The estate is currently undergoing refurbishment with new homes also being added. hese estates represent Camden's most illustrious projects, but there were a number of smaller schemes designed by a range of architects. Another duo who worked for Camden were Alan Colquhoun and John Miller who designed two small sets of flats on Caversham Road and Gaisford Street in Kentish Town (both 1979), the duo would also produced work for Haringey. Gerd Kaufmann, better known for his private houses in the suburbs, designed a number of tower and apartment blocks, like Ellerton House near Kilburn. Bill Forrest, with Oscar Palacio, designed the second stage of Highgate New Town. Stage 2a/b was a row of houses and shops in Chester Road (1978), just next to Tabori’s Stoneleigh Terrace. This addition has now been demolished to make way for a Rick Mather designed residential site. Stage 2c, a more postmodern design with timber trellises and in brick rather than concrete, still stands on the corner of Raydon Rd and Dartmouth Park Hill. Forrest had earlier designed a stepped block of flats on the Highgate Road in Kentish Town, Elsfield (1968), which also still survives. John Winter, who is better known for his private houses in the borough, designed a number of more utilitarian buildings for Camden, including the Public Cleansing Depot (1981) in Cressy Road and an Electric Dustcart Depot in Vicars Road (1981, now demolished). Other more famous names also designed buildings for the borough, Edward Cullinan, Farrell Grimshaw and James Stirling to name a few. The diversity of the designs by so many architects, whilst sticking to key principles; low rise buildings, doors that open onto a street and a private garden or terrace; provides Camden with a rich history of post war social housing. Many of the buildings created in this period still survive and are in use today. Indeed much of it is listed and widely feted as a golden age of social housing. But Camden weren't the only borough creating buildings for their inhabitants, and in the next two parts of this blog we shall look at the way the other boroughs responded to their new post-1965 powers.

References The Buildings of England- London 4: North by Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner Municipal Dreams Camden 50: The people that built Camden by Ruth Lang. |

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed