|

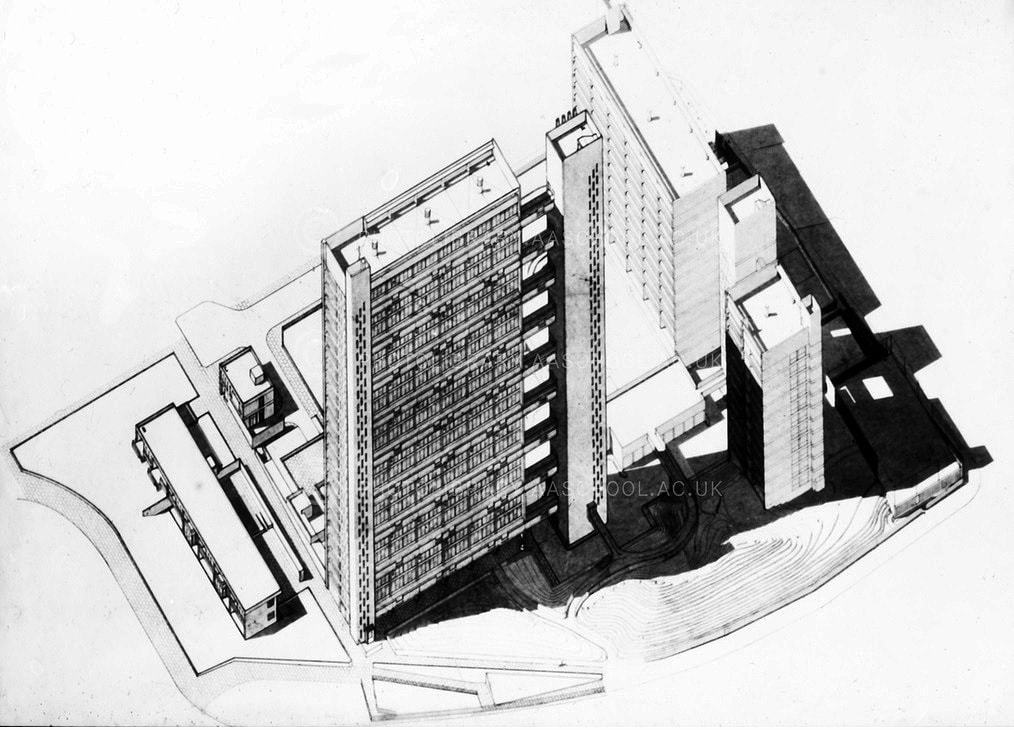

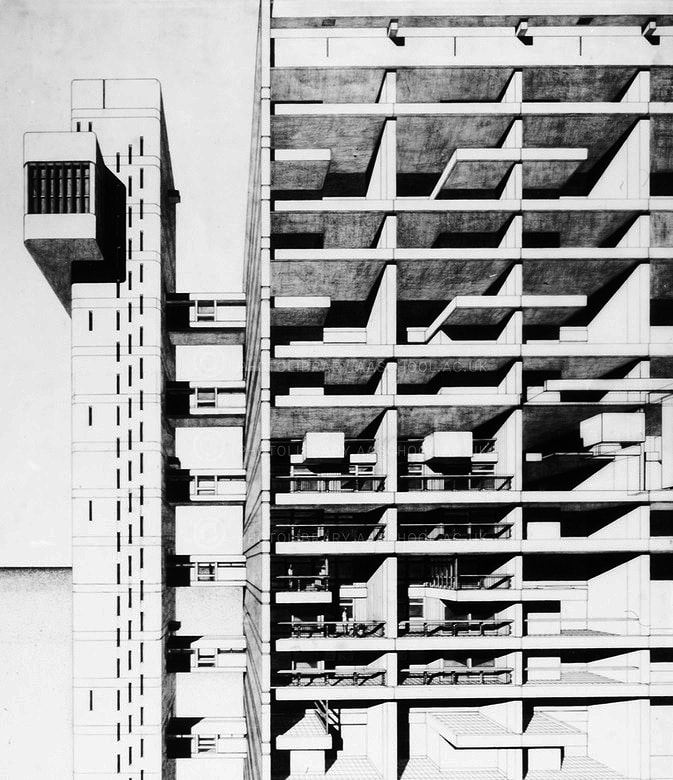

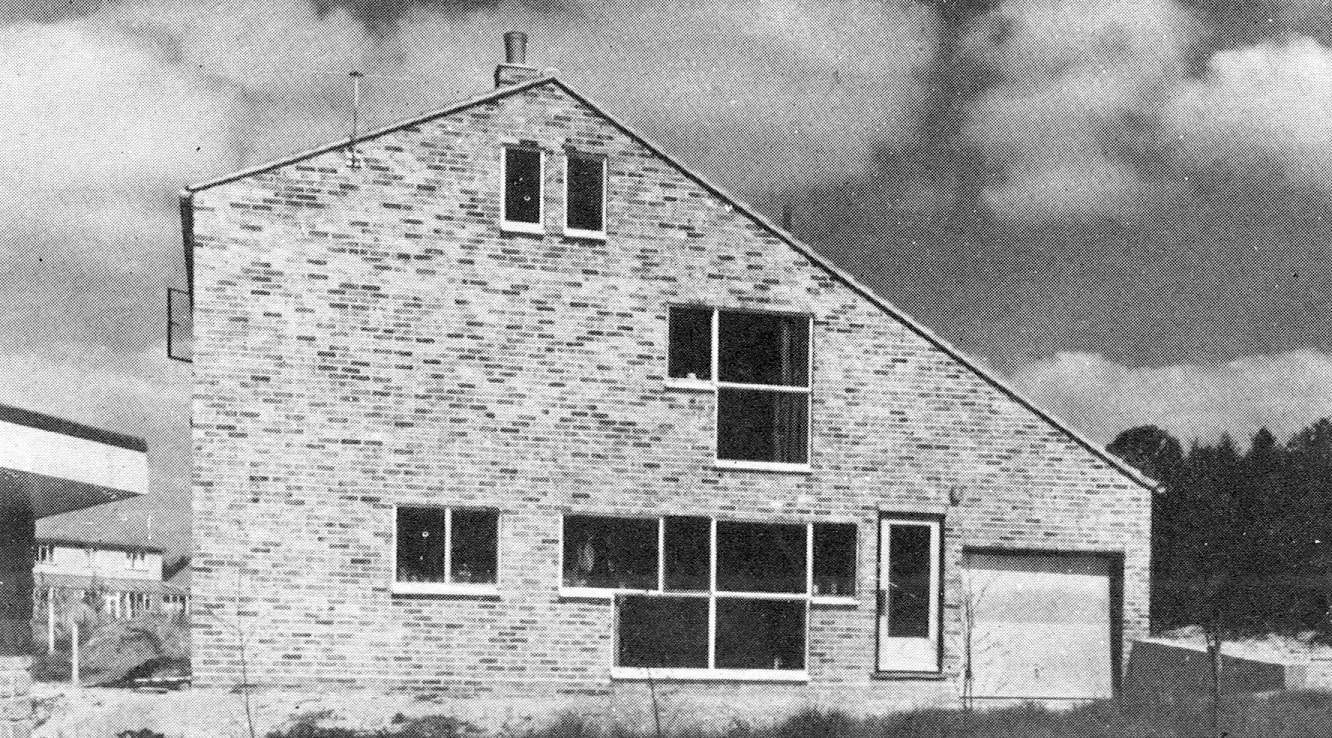

The Trellick Tower has loomed over Golborne Road in North Kensington for 50 years, now an iconic part of the neighbourhood, its profile gracing t-shirts, prints, cushions and much else. The tower is the most visible part of the Cheltenham estate, officially opened on 28th June 1972. It was designed by Erno Goldfinger, the Hungarian emigre architect, and commissioned by the Greater London Council. Goldfinger was born in Budapest, and studied under Auguste Perret in Paris before moving to London in 1934. His career in Britain before World War II consisted mainly of small projects such as shop outfitting and a couple of private houses. He came to prominence with his design for three houses in Hampstead, 1-3 Willow Road, including one for himself and his wife, Ursula Blackwell (of the Crosse & Blackwell family). The house's design caused a major planning argument between the Goldfingers, Hampstead Council and interested parties, who were aghast at a modernist design arriving in the genteel neighbourhood. The Goldfingers eventually won on appeal and the terraced houses were completed in 1938. The immediate postwar period was somewhat fallow for Goldfinger, with his hard edge designs out of step with the prevailing Scandinavian influenced Festival style. In this time he designed offices for the Daily Worker (now demolished) and a couple of primary schools. His fortune picked up in the 1960s with a commission for Alexander Fleming house at Elephant & Castle, occupied by the Ministry of Health. Goldfinger was then commissioned by the GLC to design two estates, one in Poplar known as the Balfron estate (1965), and the Cheltenham estate in North Kensington (1967). The estate was built on an 11 acre site previously occupied by demolished terraces, between the Grand Union canal and the railway line that cuts through the area. These two boundaries mean the estate is fairly compact, unlike the spread-out earlier LCC/GLC schemes like the Alton Estate in Roehampton. The centrepiece is Trellick tower, a 31 storey block in bush hammered concrete. The building's dramatic profile is created by the separation of services into a slender tower topped by a boiler house which projects like the bridge of a ship, with walkways connecting the service tower to the main block. Each flat in the tower has a balcony and large south facing windows. The deep recessed balconies, lined with cedar boarding, give the tower's facade a three dimensional effect with the play of shadows changing as the sun moves from east to west. As well as the tower, the estate was designed with five terraces of houses, two smaller blocks of flats and maisonettes, a community centre, a doctors surgery, a nursery, underground parking and an old people's home (the last two now demolished). A pub was included in the initial designs but was not built. The estate would also be home to Goldfingers office from when it was completed. The terraced houses sit along Edenham Way to the east of Trellick. They are three storeys high with an integrated garage on the ground floor, and coloured wooden panelling on the exterior. The two six-storey maisonette blocks sit just to the north of the houses, overlooking the canal. The estate was officially opened on 28th June 1972. But even at this moment of triumph, the days of the publicly commissioned concrete estate were numbered. The oil crisis and public and architectural reaction against such overwhelming use of concrete spelled the end of estates like Cheltenham. Smaller schemes made up of brick houses with gardens and irregular rooflines came to the fore and large estates were starved of funds for their upkeep. Like many postwar estates, the Cheltenham and Trellick came to signify the bleakness of modernity, despite their egalitarian intentions. After a number of incidents in the early 80s, security was improved on the estate and a residents group was formed to take over the management of the estate. The Right to Buy era also saw some of the flats pass into private ownership driving up property prices and increasing the gentrification of the area. The tower was listed in December 1998, with the remainder of the estate Grade II listed in November 2012. The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea planned to add five new blocks to the estate, designed by Haworth Tompkins, in 2018, but eventually pulled the scheme after a public outcry.

Trellick tower and the estate have come almost full circle from a vision of the future through to a relic of the past and back to a reminder of the public sphere's lofty postwar ambitions. Hopefully it will be a landmark on the western approach to London for at least another 50 years to remind bypassers of this past and possible futures.

0 Comments

Sugden House, Watford, Hertfordshire |

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed