|

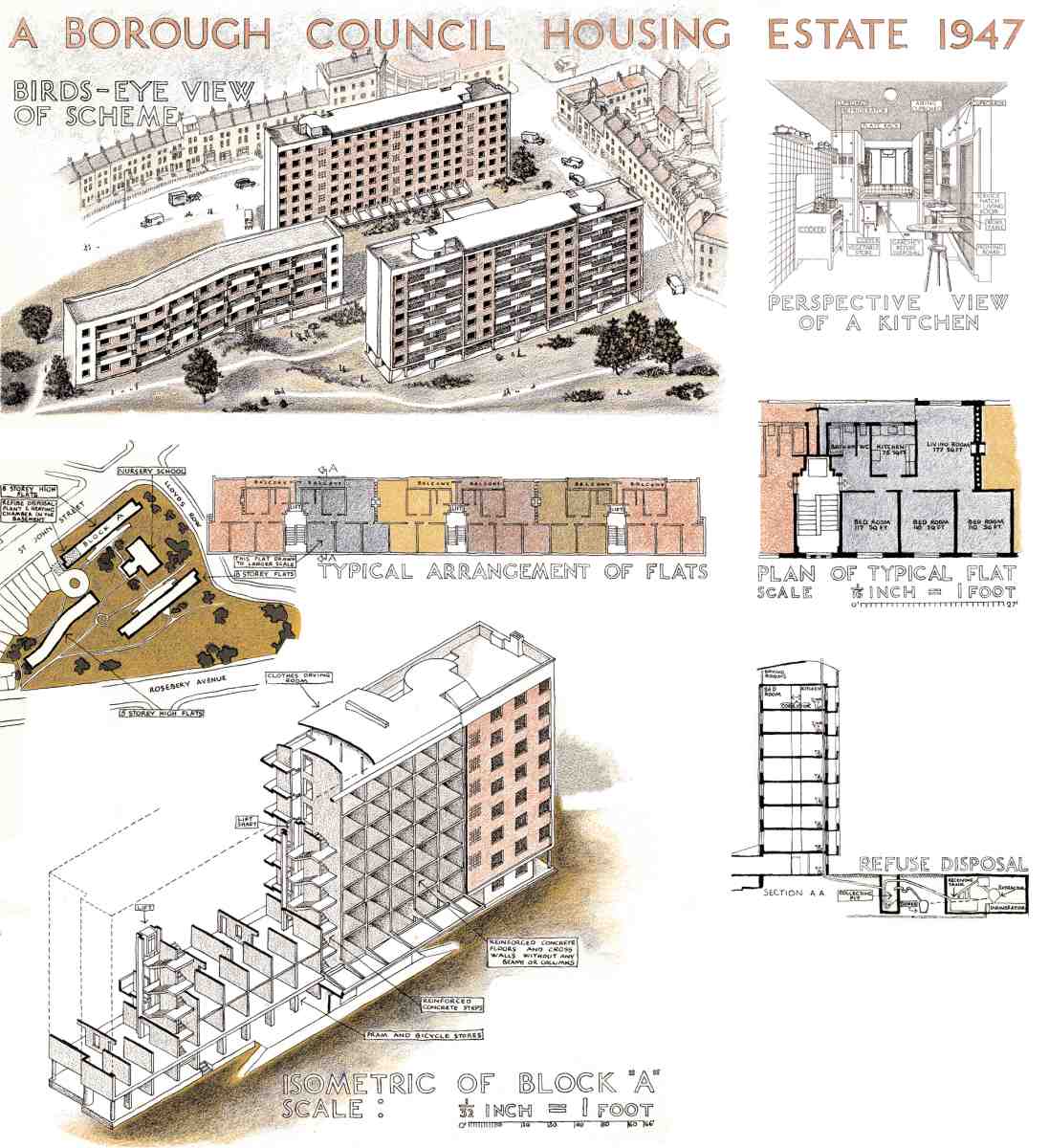

The Spa Green Estate in Islington was officially opened on April 29th 1949 by Herbert Morrison, Deputy Prime Minister. This was over 10 years since it had been originally designed, with its construction delayed by World War II. The original design was by Berthold Lubetkin and Tecton. By the time of the estates completion Tecton had been dissolved with the post-Tecton partnership of Skinner, Bailey & Lubetkin responsible for its completion. The roots of the building of Spa Green lie in the radical interwar Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury council, who looked to eradicate the debilitating effects of poverty in their area; lice, ricketts, diphtheria, etc; by the construction of new housing, medical and educational facilities. Tecton were the firm they chose to build this brave new world. The first Tecton building for the borough; the Finsbury Health Centre; opened in October 1938, and was hailed as setting new standards in modernist architecture and in public health in Britain. After this success, the borough pushed on with their plans, looking to build a number of new estates to improve housing standards. Tecton produced a plan of an estate on Rosebery Avenue (later named Spa Green) in 1938, but building was postponed due to World War II. The foundation stone was laid by then Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan in July 1946, and the estate was officially opened in 1949. The finished estate consists of three apartment blocks, two of eight storeys and one of four storeys, containing 129 flats of varying sizes. The blocks are formed from concrete eggcrate box frames, developed by Ove Arup & Partners as consultant engineers. This system allowed the buildings structure to be completed quicker than using a monolithic concrete frame. The exteriors are broken up with alternating brick or tile infill and balconies with grey ironwork. The apartments have an aspect on each side their blocks, with the bedrooms facing the away from the street towards the quieter courtyard areas. The apartments also featured Garchey refuse disposal systems, as well as central heating, fitted kitchens and heat and sound insulation. The roofs of each block feature an aerofoil shaped section designed to facilitate the drying of clothes. The estate was refurbished by Islington Borough in 1998. At the same time the Spa Green estate was commissioned and designed, Finsbury Borough also asked Tecton to design an estate a little further north, replacing Buscao Street. The first part of the estate, which became known as Priory Green, also opened in 1949 and finally completed in 1957. Once again, the estate was planned in the late 1930’s, but building was put on hold due to the war and later material shortages, with building recommencing in 1948. The largest of the three estates designed by Lubetkin for Finsbury, Priory Green is laid out to match the original street pattern and has 12 blocks of apartments, plus a circular laundry and boiler house. The blocks were built with the same method as the Spa Green buildings, and include six eight storey blocks, arranged in two groups and four four storey blocks which run in parallel. The slightly austere finish of the estate was enlivened by a concrete relief by Kenneth Hughes and internal murals by Felix Topolski. Skinner, Bailey & Lubetkin built a third estate for the borough on what had been Holford Square. The most prominent section is Bevin Court, a Y-shaped block with 130 flats. The completion ceremony was held on 24th April 1954. The interior of this block features a stunning central staircase, which Pevsner calls “one of the most exciting C20 spatial experiences in London”, as well as a entranceway mural by Peter Yates. Lenin had lived in Holford Square from in 1902-3, and Lubetkin was commissioned by the Russian Embassy to design a monument to sit in the gardens opposite his former home. It was repeatedly vandalised between its unveiling in 1941 the 1990s when it was finally placed in the Islington Museum. Two more smaller blocks make up the scheme, Holford House, a four storey block of maisonettes, and two storey Amwell House, added in 1958. The partnership, with Lubetkin concentrating on the ill fated Peterlee New Town design, produced a number of other housing estates for London boroughs. The Hallfield Estate in Paddington was planned by Tecton pre-World War II and finished by Denys Lasdun and Francis Drake between 1951-58. In what is now Tower Hamlets, they designed three estates for Bethnal Green Borough Council; the Dorset Estate (1951-64), the Lakeview Estate (1953-6) and the Cranbrook Estate (1955-65). The practice also designed a lesser known estate in Tabard Street, Southwark (1965). However, the three Islington estates remain the most famous public housing works by Lubetkin and an apt reminder of his saying that “nothing is too good for ordinary people”.

References London North- Pevsner Berthold Lubetkin: Architecture and the Tradition of Progress- John Allan Lubetkin and Tecton- Peter Coe

0 Comments

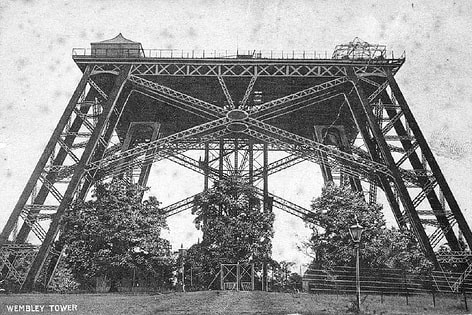

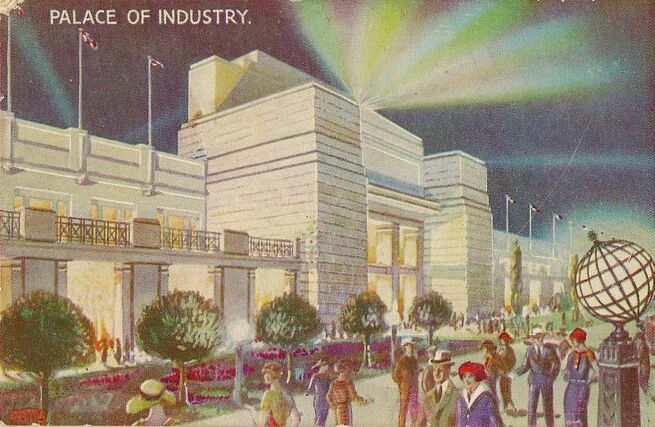

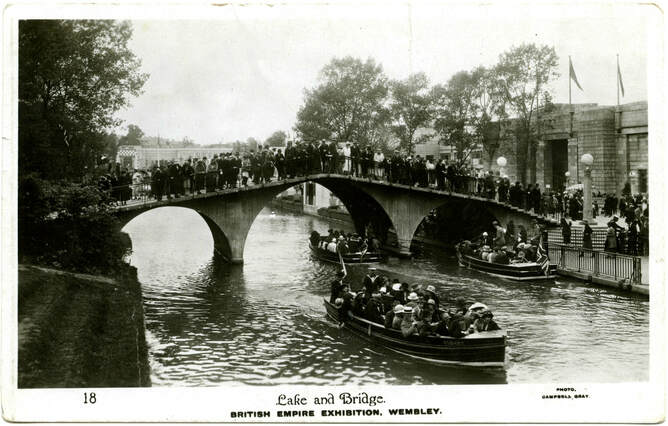

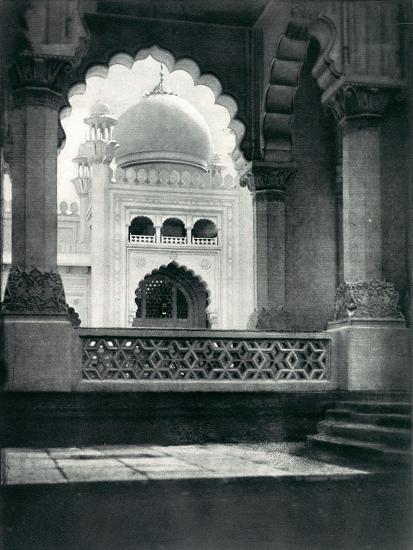

Wembley began as a settlement beside the ancient Harrow Road, part of the manor of Harrow. In 1792, Humphrey Repton was employed by the Page family to convert their farmland into a country estate, which became known as Wembley Park. In 1880 the Metropolitan Railway extended their lines through Wembley Park to Harrow, buying a portion of land from John Gray to do so. before nine years later buying the whole of Wembley Park. This would be a pivotal moment in the history of the Wembley and the suburbs, and would lead the way to the creation of Metro-Land. The Metropolitan Railway, led by Sir Edward Watkin, wanted to turn Wembley Park into a perfect suburb full of commuters using the Met to get to work in London. Of course Wembley was still some distance from what was then considered London, and so a means of attraction was needed to bring people out. This was to be Watkins Tower and the pleasure grounds built around it. Designed to exceed the newly built Eiffel Tower, the firm of Stewart, MacLaren and Dunn won the design competition with a plan for 1200 ft steel tower The tower was to include restaurants, theatres, ballrooms, a hotel and a sanitorium. Building began in 1892 with it opening to visitors four years later when the building had reached 155 ft. The design had been switched from 8 legs to 4 to save money, but that choice would led to major subsidence. After a busy beginning, the crowds dried up and the money for the construction ran out. In 1902 the tower was deemed unsafe, and it was decided to demolish the half built tower, with the foundations being dynamited in 1907. The area around the pleasure ground started to be developed, with houses being built to form Wembley Park Village, all in the tudorbethan style. The next event to draw people to Wembley was the British Empire Exhibition of 1924. The exhibition was planned with the stated aim of an exhibition "... to enable all who owe allegiance to the British flag to meet on common ground and learn to know each other.”. The design of the exhibition buildings was largely by Maxwell Ayrton and John Simpson, with Owen Williams appointed as the engineer. They designed and built a range of buildings in the Beaux Arts style, including national pavilions for almost every country in the Empire, as well as pleasure gardens, shops, restaurants and an amusement park. However the centrepieces of the site were to be the Palaces of Industry, Arts, Engineering and Horticulture, alongside a national sports stadium. The national sports stadium proved to be the most famous building constructed for the exhibition, the Empire Stadium. Known worldwide as Wembley Stadium, the home of English football. The stadium and its iconic towers lasted until 2003 when it was demolished to make way for the new stadium on the same site by Foster + Partners and Populous. The national pavilions reflected each countries architectural styles, with Buddhist temples , Chinese markets and African huts appearing in the Middlesex countryside. The design of the Palaces were much less exotic but just as impressive. When completed, the Palace of Engineering was the largest reinforced concrete building in the world. It covered 13 acres and featured five internal railway lines to help move the exhibits. Like all the buildings in the exhibition, the Palace of Engineering was intended to be temporary, but managed to survive until the 1970’s. The Palace of Arts lasted until 2006, when it was demolished to make way for a car park. The Palace of Industry managed to last until 2013. slightly smaller the the Palace of Engineering, at 10 acres, it is made up of a number of halls enclosed with glazed pitched roofs. The pre-cast concrete was reinforced and partly painted and channelled to appear like stone. It was the first building in Britain to use concrete for external as well as internal support, and despite its classical style, it had a hulking, modern look. The site also included a bridge, praised by Ian Nairn in his “Nairns’ London”, “a concrete bridge moulders away among the weeping willows and beer cans. Crisp and angular, it must be one of the best things we did in the twenties- true English modernism”. The only two remnants of the exhibition are what is left of the India Pavilion and a refreshment hall. The India Pavilion was jointly modelled on the Jama Masjid in Dehli and the Taj Mahal in Agra and designed by the firm of Sir Charles Allen and Sons. Inside it was divided into 27 courts each focusing on products from the 27 provinces of India. Unfortunately the centrepiece central dome section is no longer there, but the the flanking buildings remain. These buildings have been turned into businesses, one is Latif Rugs, the other is Stonemanor Ltd. A bit further west is the former refreshment hall, now home to several companies, including Rubicon the soft drinks manufacturer. The exhibition itself had a great impact on the expansion of Wembley and Metro-Land. Despite grumbles that the site was too far from central London, over 10 million people visited the exhibition in its first 6 months, and nearly 27 million made the journey before the close of the exhibition. For many of these visitors it was their first visit to the Metro-Land suburbs, as Sir John Betjeman noted, previously Wembley was “an unimportant hamlet where the Met didn’t bother to stop” but afterwards it became a growing suburban centre. To compare the numbers; in 1921 Wembley had a population of 18,239, 10 years after the exhibition it contained 121,600 people, an increase of 552%

(For comparison the 2011 population was 90,045). The British Empire Exhibition has all but disappeared, with only a few remaining relics, subsumed under Wembley’s ferocious bid to reinvent itself as the Stratford of the West. The exhibition is not as fondly remembered as the Festival of Britain 27 years later, it’s title and aim seeming antiquated in the 21st century compared to the futuristic buildings that appeared on the South Bank. But it is a shame that some of the buildings by Ayrton and Williams have not been preserved, considering their pioneering construction, as well as their place in the growth of the suburbs. References Phantom Architecture- Philip Wilkinson Semi Detached London- Alan A. Jackson Nairn’s London- Ian Nairn Modern Buildings in London- Ian Nairn London 3: North West- Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner Owen Williams- David Yeomans and David Cottam These notes were first written for the 20th Century Society tour "Wembley and the Making of Metro-Land" held onSaturday 27th October 2018. |

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed