|

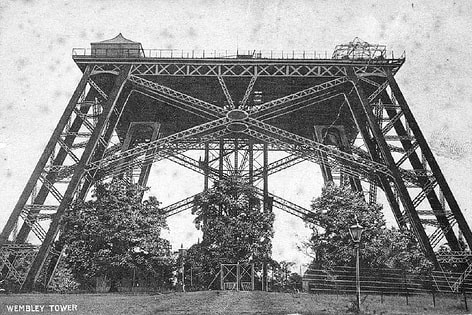

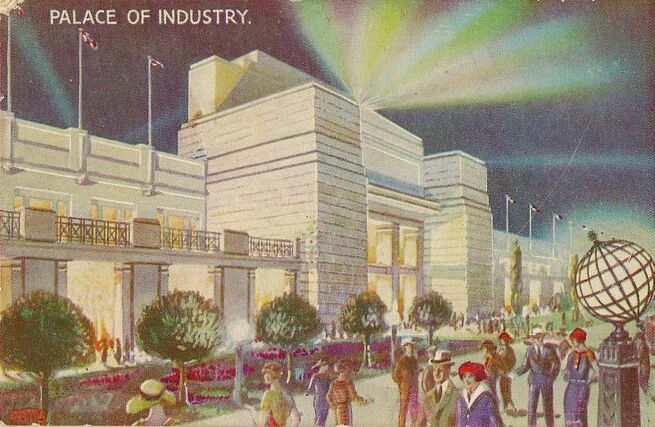

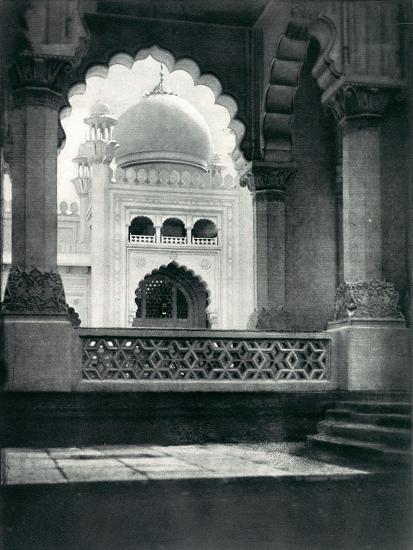

Wembley began as a settlement beside the ancient Harrow Road, part of the manor of Harrow. In 1792, Humphrey Repton was employed by the Page family to convert their farmland into a country estate, which became known as Wembley Park. In 1880 the Metropolitan Railway extended their lines through Wembley Park to Harrow, buying a portion of land from John Gray to do so. before nine years later buying the whole of Wembley Park. This would be a pivotal moment in the history of the Wembley and the suburbs, and would lead the way to the creation of Metro-Land. The Metropolitan Railway, led by Sir Edward Watkin, wanted to turn Wembley Park into a perfect suburb full of commuters using the Met to get to work in London. Of course Wembley was still some distance from what was then considered London, and so a means of attraction was needed to bring people out. This was to be Watkins Tower and the pleasure grounds built around it. Designed to exceed the newly built Eiffel Tower, the firm of Stewart, MacLaren and Dunn won the design competition with a plan for 1200 ft steel tower The tower was to include restaurants, theatres, ballrooms, a hotel and a sanitorium. Building began in 1892 with it opening to visitors four years later when the building had reached 155 ft. The design had been switched from 8 legs to 4 to save money, but that choice would led to major subsidence. After a busy beginning, the crowds dried up and the money for the construction ran out. In 1902 the tower was deemed unsafe, and it was decided to demolish the half built tower, with the foundations being dynamited in 1907. The area around the pleasure ground started to be developed, with houses being built to form Wembley Park Village, all in the tudorbethan style. The next event to draw people to Wembley was the British Empire Exhibition of 1924. The exhibition was planned with the stated aim of an exhibition "... to enable all who owe allegiance to the British flag to meet on common ground and learn to know each other.”. The design of the exhibition buildings was largely by Maxwell Ayrton and John Simpson, with Owen Williams appointed as the engineer. They designed and built a range of buildings in the Beaux Arts style, including national pavilions for almost every country in the Empire, as well as pleasure gardens, shops, restaurants and an amusement park. However the centrepieces of the site were to be the Palaces of Industry, Arts, Engineering and Horticulture, alongside a national sports stadium. The national sports stadium proved to be the most famous building constructed for the exhibition, the Empire Stadium. Known worldwide as Wembley Stadium, the home of English football. The stadium and its iconic towers lasted until 2003 when it was demolished to make way for the new stadium on the same site by Foster + Partners and Populous. The national pavilions reflected each countries architectural styles, with Buddhist temples , Chinese markets and African huts appearing in the Middlesex countryside. The design of the Palaces were much less exotic but just as impressive. When completed, the Palace of Engineering was the largest reinforced concrete building in the world. It covered 13 acres and featured five internal railway lines to help move the exhibits. Like all the buildings in the exhibition, the Palace of Engineering was intended to be temporary, but managed to survive until the 1970’s. The Palace of Arts lasted until 2006, when it was demolished to make way for a car park. The Palace of Industry managed to last until 2013. slightly smaller the the Palace of Engineering, at 10 acres, it is made up of a number of halls enclosed with glazed pitched roofs. The pre-cast concrete was reinforced and partly painted and channelled to appear like stone. It was the first building in Britain to use concrete for external as well as internal support, and despite its classical style, it had a hulking, modern look. The site also included a bridge, praised by Ian Nairn in his “Nairns’ London”, “a concrete bridge moulders away among the weeping willows and beer cans. Crisp and angular, it must be one of the best things we did in the twenties- true English modernism”. The only two remnants of the exhibition are what is left of the India Pavilion and a refreshment hall. The India Pavilion was jointly modelled on the Jama Masjid in Dehli and the Taj Mahal in Agra and designed by the firm of Sir Charles Allen and Sons. Inside it was divided into 27 courts each focusing on products from the 27 provinces of India. Unfortunately the centrepiece central dome section is no longer there, but the the flanking buildings remain. These buildings have been turned into businesses, one is Latif Rugs, the other is Stonemanor Ltd. A bit further west is the former refreshment hall, now home to several companies, including Rubicon the soft drinks manufacturer. The exhibition itself had a great impact on the expansion of Wembley and Metro-Land. Despite grumbles that the site was too far from central London, over 10 million people visited the exhibition in its first 6 months, and nearly 27 million made the journey before the close of the exhibition. For many of these visitors it was their first visit to the Metro-Land suburbs, as Sir John Betjeman noted, previously Wembley was “an unimportant hamlet where the Met didn’t bother to stop” but afterwards it became a growing suburban centre. To compare the numbers; in 1921 Wembley had a population of 18,239, 10 years after the exhibition it contained 121,600 people, an increase of 552%

(For comparison the 2011 population was 90,045). The British Empire Exhibition has all but disappeared, with only a few remaining relics, subsumed under Wembley’s ferocious bid to reinvent itself as the Stratford of the West. The exhibition is not as fondly remembered as the Festival of Britain 27 years later, it’s title and aim seeming antiquated in the 21st century compared to the futuristic buildings that appeared on the South Bank. But it is a shame that some of the buildings by Ayrton and Williams have not been preserved, considering their pioneering construction, as well as their place in the growth of the suburbs. References Phantom Architecture- Philip Wilkinson Semi Detached London- Alan A. Jackson Nairn’s London- Ian Nairn Modern Buildings in London- Ian Nairn London 3: North West- Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner Owen Williams- David Yeomans and David Cottam These notes were first written for the 20th Century Society tour "Wembley and the Making of Metro-Land" held onSaturday 27th October 2018.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed