|

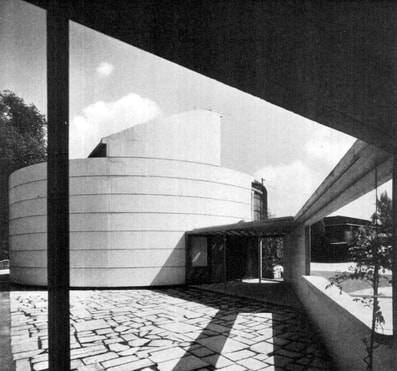

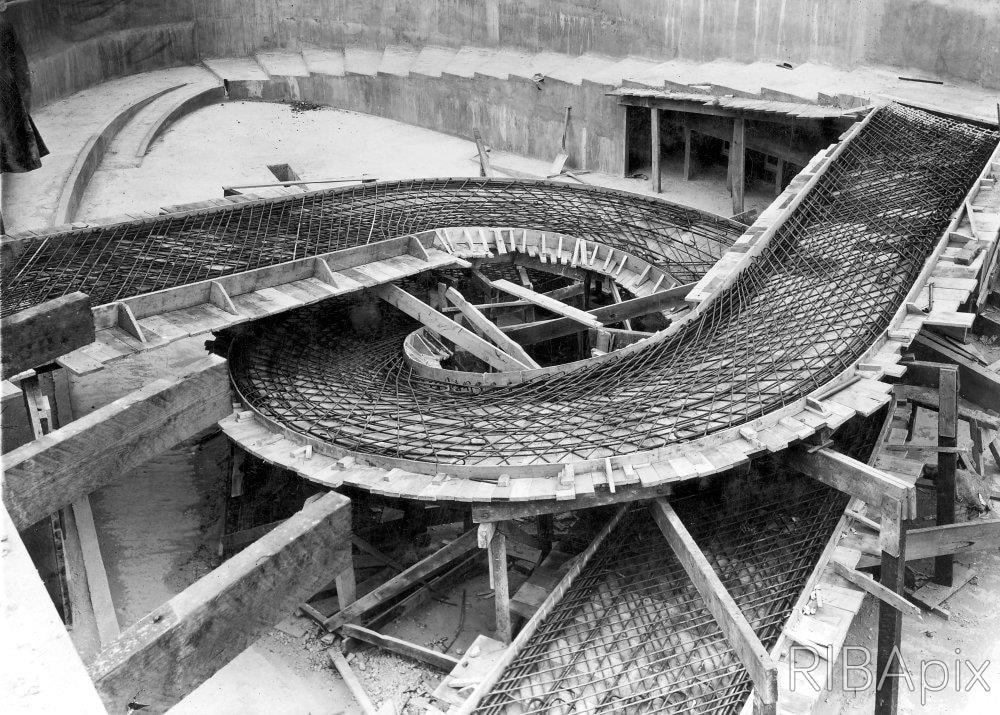

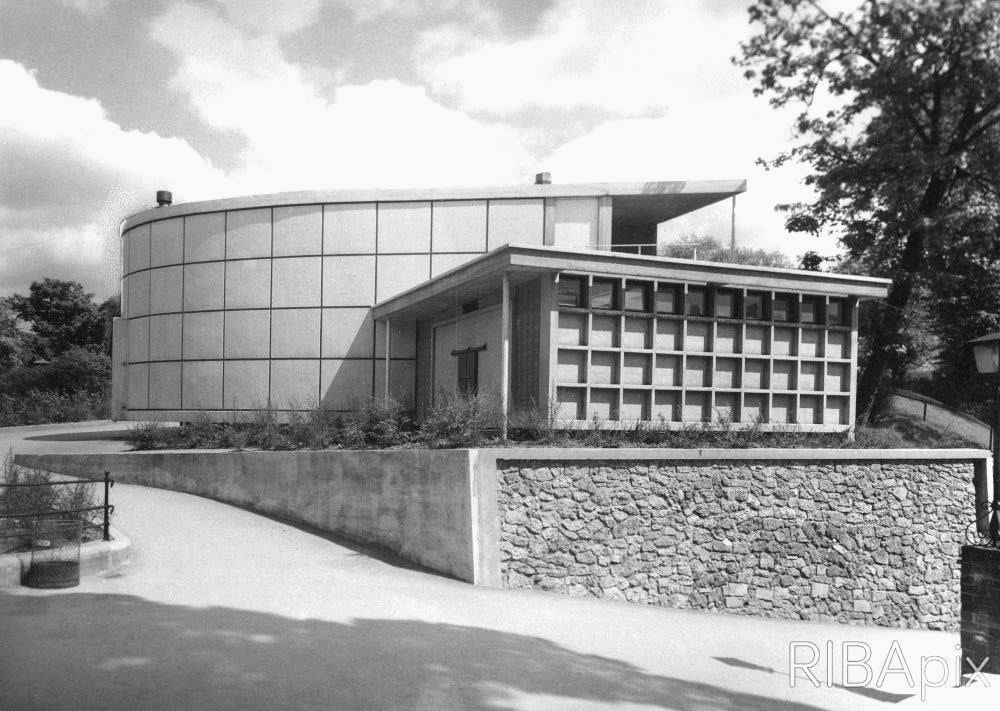

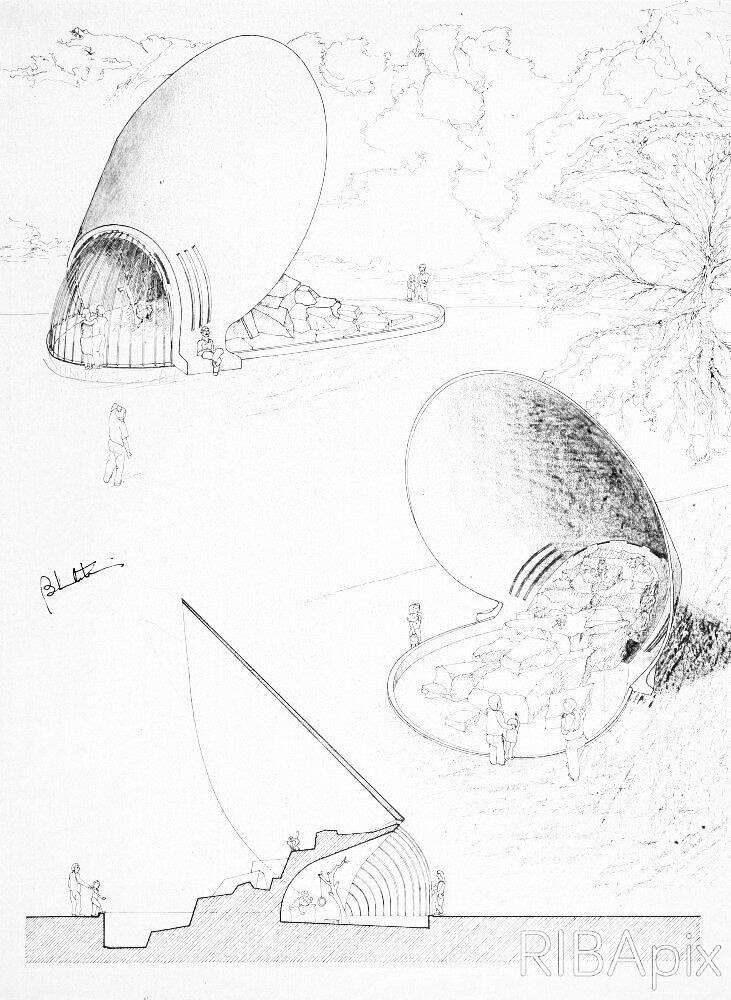

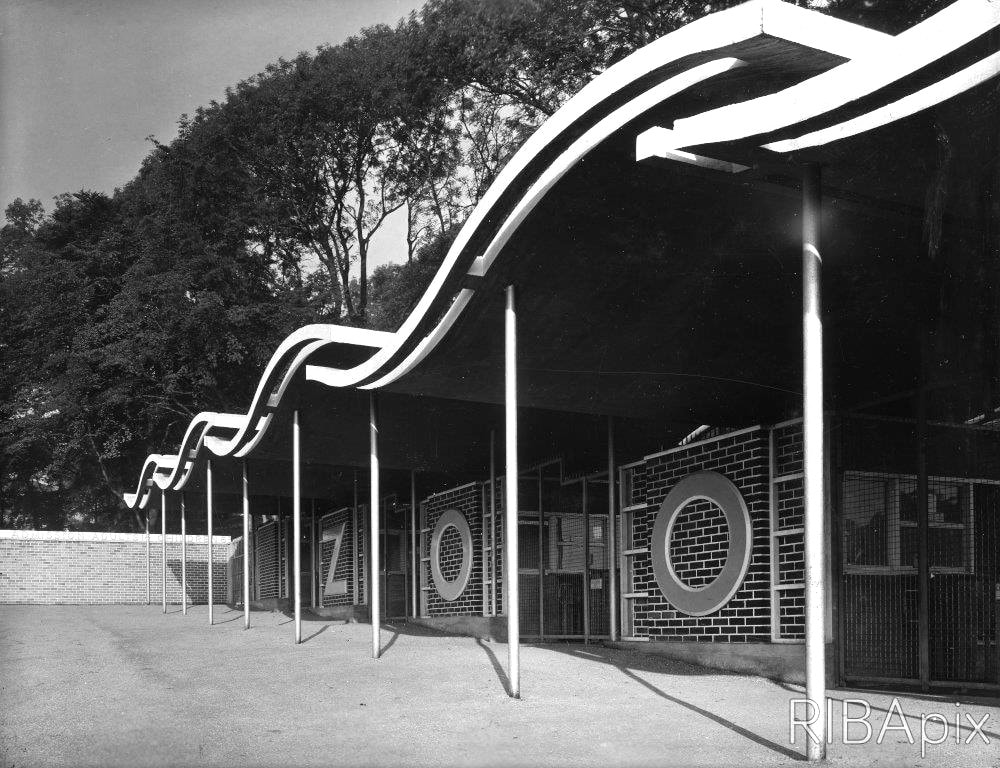

London Zoo opened in April 1828 as a scientific study centre, with grounds laid out by architect Decimus Burton. It opened to the public in 1847, with the grounds expanding and new animal enclosures and public buildings being added by Peter Chalmers Mitchell and John James Joass, such as the Mappin terraces, designed to provide a mountainous habitat for bears and other animals. In 1932 Berthold Lubetkin and his Tecton partnership were given a commission by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) to design a Gorilla House, a project that would lead to a fruitful period of modernist zoological design. The Gorilla House consists of a circular plan, half enclosed and half open.The caged, open half can be insulated by a moving screen, allowing the interior climate to be kept warm enough to mirror conditions in the Congo, original home of the Gorillas. The closed half of the drum is constructed of reinforced concrete, with an asphalt flat roof. Alongside Charles Holden’s underground stations (of which some it mirrors in plan) it was one of the first public modernist buildings in Britain. The enclosure was opened on 28th April 1933. The following year Tecton produced their second building for the zoo, one that would create headlines around the world and come to signify both the positives and negatives of modernist design. The Penguin Pool consists of an elliptical pool containing interlocking spiral ramps, all in brilliant white reinforced concrete. The upper part of the pool has framed viewing areas supported by thin steel columns. The ramps have no such similar support, curving for 14 meters. Their design was made in cooperation with Ove Arup, who would work on many Lubetkin & Tecton projects in the 1930s, with Felix Samuley carrying out the structural analysis. Famously of course the penguins were moved in 2004 and the pool left empty, as the structure was not felt to be a natural environment for them. Tecton also designed a combined entrance gate, office and kiosk for the northern side of the zoo in 1938. Another building Tecton designed for the zoo was the Studio of Animal Art. The building was the first part of what would have been a complex of buildings used to investigate and research animal behaviour. The studio, the only part built, featured a studio to seat 25 students and two separate workrooms. The studio section contained a cage where animals would be placed for the students to observe. A separate cinema and lecture hall were planned but never built, and the studio was demolished in the 1960s to make way for the Nuffield Institute building by Casson and Conder, who also designed the new Elephant and Rhino House in 1965. Tecton had designed an elephant and rhino house for the zoo, but building was stopped at the outbreak of World War II and never completed. At the same time that Tecton were designing the Penguin Pool in London, they were also given the commission to design a number of buildings at Whipsnade Zoo in Bedfordshire, also owned by ZSL. Tecton designed an elephant house, a giraffe house, a kiosk and a cafe for Whipsnade. Only two of these four buildings still survive, with the giraffe house and the kiosk demolished. The timber giraffe house was the first completed of the four buildings, built in a rush to accommodate the arrival of the animals who were en route by sea. The local building firm employed to complete the structure did not follow Tectons designs exactly, with the public viewing area being reduced in size. After several modifications through the years, the building was demolished. Another Tecton design that wasn't built was a Gibbon House at Whipsnade, that featured an amphitheatre shaped canopy that would have amplified the Gibbon’s calls over the park. Neither of the two surviving Tecton buildings at Whipsnade are used for their original purpose. The concrete elephant house, made up of a series of circular stalls, was designed for younger elephants, with the older, larger animals kept elsewhere. Like the penguin pool in London, the elephant house was later deemed unsuitable and the elephants were moved and the building left empty. The restaurant is an annexe to the 18th Century farmhouse in the park, that served as the dining area. The new structure featured a wall of glass bricks for the entrance and views out to the park from two of the other three walls. The wall of glass brick was an idea Lubetkin and Tecton reused on their Finsbury Health Centre in 1938. The building now houses small primates. Tectons third zoo commission would prove to be their largest. Dudley Zoo was opened in the grounds of Dudley Castle, owned by the Third Earl of Dudley. Tecton designed thirteen buildings for the zoo, between 1935 and 1937, to house a range of animals, many moved from Oxford Zoo which closed in 1936. Twelve of these structures are now listed by Historic England, with only the penguin pool demolished, due to salt water corrosion, in 1979. The animal enclosures number a birdhouse, a bear ravine, an elephant house, a seal lion pool and a polar bear pit. The buildings for visitors that Tecton designed include the famous curved entrance, the Castle restaurant, two cafes and a number of kiosks. The buildings had all deteriorated by the start of the 21st century, and following funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund, refurbishment was undertaken from 2012.

Tecton designed a number of highly influential buildings throughout the short life of the practice in the 1930s. Buildings like the Highpoint apartment in Highgate and the Finsbury Health Centre would set new standards for British modernism and be talked about by architects throughout the world. However the buildings that would embed them in the public's imagination were their buildings for animals. Designs such as the Penguin pool at London Zoo would often be the public's first experience of international style modernism, and although not always successful in terms of the original purpose, i.e. as homes for the animals, they remain part of the country's cultural imagination.

1 Comment

|

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed