|

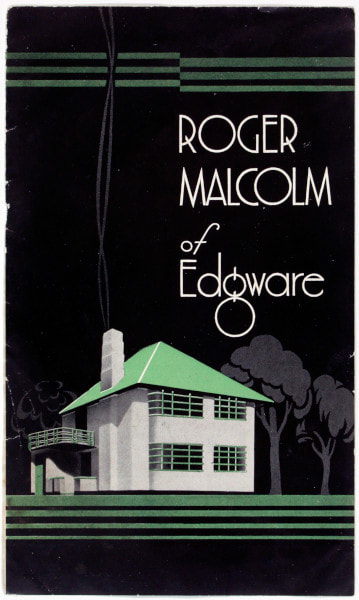

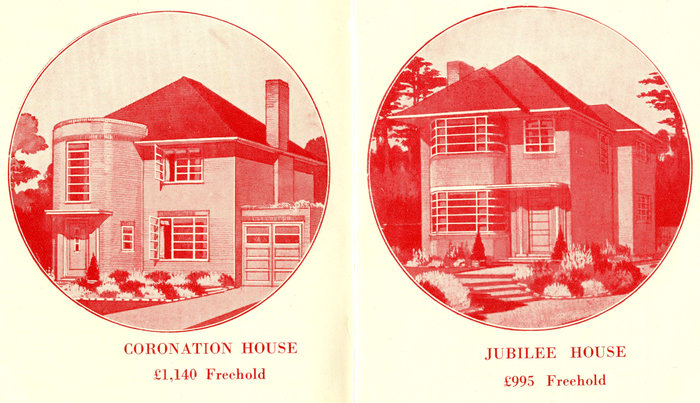

To celebrate the launch of our new mini guide; Speculative Suburban Houses 1928-38, we have a guest blog from Joe Mathieson on the Suntrap house, the developers response to art deco and modernism in the 1930s. If you were looking for a new home in outer London in the mid-1930s, you might have come across an advert for the developer Thomas Currey’s Willow Road Estate in Enfield. Designed as ’new world homes in an orchard setting’, they were built near ‘open country’ and yet ‘just outside the town’. Metroland, the piecemeal interwar suburban development programme, had sprawled eastward, far beyond its origin in West London, to find itself around the corner from Enfield Town station. The houses of Willow Road were suntrap houses. The suntrap house is a domestic typology found across London originating in the early 1930s. Characterised by a bay window with curved steel units that ‘trap the sun’, it is generally a semi-detached building with a traditional pitched roof. The suntrap represented a tentative modernist offshoot of a speculative house building tendency that specialised in the mock-Tudor or ‘Jacobethan' styles. Like those particular brands of revivalism, the suntrap catered towards well-to-do working class and lower middle-class families aspiring to a house of their own. Suntraps are found all across North London - Gidea Park, Belsize Park, Cockfosters, Edgware, Oakwood, Pinner, Clay Hill and Hampstead Garden Suburb. At the same time, they have been dismissed as a minor footnote in interwar architectural history, typifying an architectural compromise that pleased few. But suntraps are a thing of beauty. They also throw up thought-provoking questions of authorship, mass production and popular taste within twentieth century British architectural culture. FormSuntraps generally contain bay windows over two floors with Crittall units that curve on either side of the adjoining front bays. Roofs are traditionally hipped, with shared chimneys to the party wall. While typically coated in white render, often they contain brick side elevations or ground floor brick frontages. The concrete door canopy very often reflects the moderne curves of the glass, while the door will usually be heavily glazed with a ‘sunburst’ symbol. Some suntrap houses still have chevron motifs in their windows, a hallmark of the Crittall brand. A typical suntrap’s scale is similar to many of the mock-Tudor builds whose streets they share. The hall was designed wider than in most pre-war houses, allowing staircases to be brought forward to the door. They would have had separate dining and living rooms on the ground floor. The decreasing fashion of servants in the interwar period, alongside the clientele that the suntrap was expected to attract, meant that the kitchens were almost always integrated into the main house unlike in previous eras. On the second floor would be two or three bedrooms. Suntraps came loaded with all mod cons - electricity, hot water, and a flushing toilet. The sweeping windows would absorb sunlight in an age where sun rays were widely seen to be therapeutic and health-giving. With a driveway fit for one or two motorcars, they perfectly encapsulated the aspirations and necessities of Metroland. AuthorshipA handful of architectural firms designed suntrap houses. The key partnership for their evolution was Welch, Cachemaille-Day and Lander, comprising Herbert Welch (1884-1953), N. F. Cachemaille-Day (1896-1976) and Felix Lander (1898-1960). It was likely Welch that led the initiative in these designs. He worked on the first set of suntraps at Old Rectory Gardens, Edgware in 1932, in partnership with the developer Roger Malcolm. C. M. Crickmer (1879-1971) followed Welch’s lead, developing them around the middle of the decade. G. G. Winbourne (1892-1947) developed suntraps into groupings more fitting to southern Europe, with flat roofs and balconies. The suntrap was a reproducible type to which minor alterations could be made depending on the client, or, as was more often the case, their predicted desires. Architectural drawings could also be made for a particular range of iterations of suntrap and repeated as many times as the plot of land allowed. Such a ‘Universal Plan’ provided the bread and butter work of many architects. Ossulton Way in Hampstead Garden Suburb is one such example. Designed in 1934 by Welch, Cachemaille-Day and Lander, the north side of the close contains detailed plans of the houses labelled types A - E. The outlines of the houses are drawn on the south side but instead of detailing the internals instead read ‘Repeat’ for each letter. The houses’ ‘identikit’ features made them expedient for speculative builders seeking to forego costly architects’ fees and expedite the overall construction process. Builders who worked on suntraps included Coombs Construction, Morrell’s and Haymills. The architect C. Bertram Parkes noted in the RIBA journal in the mid-1930s that architects were generally ‘not employed when houses of this [semi-detached] type are erected’. TasteSuntrap houses have been dismissed as ‘modernistic’ - rushed attempts at modernism proper. In 1942 the critic Anthony Bertram argued they were traditional houses dressed up by builders with a cheap streamlined flourish: ‘bogus modern, as the Tudoristic is bogus Tudor’. For the cartoonist and historian Osbert Lancaster, suntraps represented a ‘nightmare amalgam of elements’ betraying a ‘misunderstanding of the Corbusier-Gropius school’. For these critics the suntraps’ external stylistic blending was often reflected in the interior design choices of their inhabitants, combining contemporary design, of whatever quality, with furniture and fittings from the pre-war era. The interior and exterior aesthetics of the suntrap in its heyday fits neatly into what poet John Betjeman called Jazz Moderne. Inspired by interwar American pop culture, the phrase evokes glamour and fashion on the one hand; ephemerality and lack of authenticity on the other. The suntrap is seen to encapsulate a fundamental misunderstanding of the lessons of the Machine Age as held by the purist avant-garde. But the label fails to capture the ambitions and dreams of the aspirational suntrap homeowner of the time. For these buyers, the house was something much more (or perhaps much less) than Le Corbusier’s notion of ‘a machine for living in’. LegacyDeveloper-driven suburbs were condemned at the international modernist congress CIAM (Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne) in the mid-1930s as an ‘urbanist folly’; ’squalid antechamber[s] of the city’. Today such sentiments have lost some of their edge. Interwar suburbs are the backdrop of daily life for countless citizens. Three million houses were built around the suburbs during the interwar period, the majority of them in London. The average semi-detached, suntrap or otherwise, is as aspirational now as then. Situated among the suburbs’ vast expanses, suntraps represent a dalliance with modernism that contrasts nicely with their more conservative counterparts. But their ‘jazz’ inclinations also remind us that not all modernist architecture is pure and ‘true to its age’. Much of it was profit-seeking, stylistically awkward, and - yes - populist. Suntraps are relatively unprotected entities from a conservation standpoint. They are often the victims of unsightly extensions and refurbishment work - oversized dormer windows, unsympathetic render, and most notably, window replacements in uPVC plastic that omit the unique curve of their bays. A greater recognition of the suntrap might go some way to persuading people to preserve them, and to celebrate their oddity as houses both attractive and unpretentious. Joe Mathieson is the Architectural Support Officer at the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, and a Twentieth Century Society volunteer Speculative Suburban Houses 1928-38 is the third in our series of Mini Guides, each exploring the modernist buildings of a particular location or architect. Mini Guide No.3 surveys the speculative suburban house of the 1930s, when developers used art deco and modernism to sell houses to the masses. Get your copy HERE

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed